Design Calendar | Designer | Knoll | Producer

And take good care of Florence, Eliel Saarinen did: so much so that she advanced to become one of the most important protagonists in the development of post-war furniture, textile and interior design.

Born on May 24th 1917 in Saginaw, Michigan, to the emigrant Swiss engineer Frederick Schust and his American wife Mina Matilda, Florence Schust had a turbulent childhood: her father died in 1923, aged just 42, and when her mother subsequently became seriously ill she appointed a local banker as Florence's legal guardian. The above addressed Judge Emile Tessin. Following her mother's untimely death in 1931 Florence Schust entered Kingswood School Cranbrook as a boarder, before in 1934 enrolling at the neighbouring Cranbrook Academy of Art.

According to Florence2, she was introduced to architecture and design by Kingswood's art director Rachel de Wolfe Raseman, before a house design assignment brought her into contact with both Cranbrook's director, the Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, and his wife, the textile designer Loja Saarinen. Eliel, aware of Florence's intentions to follow an architectural career, suggested she attend Cranbrook as a precursor to studying, and under Eliel Saarinen's guidance Florence not only developed her understanding of architecture but became acquainted with both established creatives, such as the celebrated Swedish sculptor Carl Milles, and also younger, rising talents: Harry Bertoia, Eero Saarinen and Charles Eames. To name but three.

In addition to nurturing her educationally the Saarinens also took Florence Schust under their wing, making her in all but title part of their family, and taking her with them on their annual summer holiday to Europe.

Recalling one such holiday, Florence notes, "after two years at the Art Academy, it was time to move on for a more formal education at a qualified architectural school. I was as usual spending the summer months at Hvitrask the Saarinen's home in Finland. Alvar Aalto was a guest for lunch and suggested the Architectural Association in London"3

And so in autumn 1938 to London and the Architecture Association she went: the outbreak of World War II enforcing her return to America where she initially served as an apprentice to Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer in Cambridge, Massachusetts, before moving on to the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago where she completed her studies under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Thus, upon graduating in June 1941, and at just 24 years old, Florence Schust had an established international network which stretched from some of the leading protagonists of European modernism to some of those who would define the American response.

In effect, all she needed was a platform.

Moving to New York in 1941 Florence Schust jobbed for several architectural practices before her path crossed that of Hans Knoll: scion of a German furniture dynasty, in the process of establishing his own furniture company in New York, a furniture company specialising in the modern European designs Hans had, in effect, grown up with. And in need of an interior designer.

Florence Schust took up the challenge and in 1943 the Knoll Planning Unit was established under her direction, an institution which in 1945 Arts & Architecture magazine called “the force which integrates all the various related activities of the company, with the objective of placing well designed "equipment for living" within the reach of a large consumer market”4, and an institution which through its success in doing just that became the cornerstone on which Knoll Associates was built.

While Florence concentrated on the design, Hans was responsible for the business aspects, a professional relationship which became a private relationship when Florence and Hans married in 1946.

The first projects the Knoll Planning Unit undertook were the company's own offices and showrooms, spaces which not only allowed the company to introduce its furniture but which allowed Florence Knoll to introduce her thinking on space and the relationships between furniture and user. The regular, positive, reviews of the showrooms in the specialist architecture magazines of the day and early, high profile, widely reported, commissions, including the offices of Columbia Broadcasting Systems, CBS, in New York or the headquarters of the Connecticut General Life Insurance in Bloomfield, Connecticut, further helping promote the Knoll philosophy.

Until the 1930s American interiors had largely been the domain of interior decorators. The Knoll Planning Unit was one of the first to move away from "decorating" a space to "designing" it, to focus less on the object per se and more to question how the object can satisfy the needs of the users and help optimise and humanise the space.

In a 2001 interview Florence Knoll stated "I was architecturally trained to think logically about space"5, and in terms of her interior designs, and for all in terms of her office designs, that area where Knoll first established itself, that meant breaking with the standards of day, and for all the traditional, heavy furniture and even heavier, rigid, layouts.

Through, for example, lighter, more reduced furniture, considering how lighting and ventilation were integrated, using partition walls to break up space and colour to create atmosphere, Florence Knoll not only designed lighter, more ergonomic spaces which made more of what was available, but which also corresponded to both the contemporary architecture in which her clients invariably found themselves, and also the modern, progressive, image the company's were looking to promote. And in doing so radically changed understandings of not only office design but also the relationship between architect, designer, manufacturer and client, and thus paved the way for our contemporary understandings of office design.

In addition to changing ideas of office design, Florence Knoll also revolutionised the process of designing office spaces. Whereas previously firms had simply bought furniture, Florence Knoll started with an analysis of the space, its pros and cons, before interviews were undertaken, the requirements of the users defined, acoustics assessed, traffic flows analysed and subsequently a plan presented as a 3D paste-up. As Bobbye Tigerman notes6, whereas the paste-up was known in fashion and stage design, Florence Knoll was the first to adapt if for interior design: using textile cut offs to symbolise different objects in a scale model of the space, and thus allowing for a simple, instantaneous visualisation of the concept, without getting caught up in details. Whereas today such a process, augmented by the advantages of 3D planning software, is standard. Then it was anything but.

The inaugural Knoll furniture collection in 1941 was largely the work of Jens Risom, in 1945 came licensed works by the Danish designer Abel Sorenson, and with commissioned works by Cranbrook alumni Ralph Rapson the first use by Florence Knoll of her network and Cranbrook connections. A network and connections she would increasingly turn to as she sought to form Knoll into a company producing furniture which corresponded to her understanding of contemporary design and the needs of contemporary offices and homes.

Yet despite establishing a roster of international designers including, and amongst many others, Eero Saarinen, Isamu Noguchi, Pierre Jeaneret, Harry Bertoia, Mies van der Rohe and Ilmari Tapiovaara, the greatest proportion of Knoll's furniture throughout the 1940s and 50s was designed by Florence Knoll. Bobbye Tigerman states 50% based on an undated interview with Florence Knoll in the Knoll archives.7

The reason for Florence Knoll's industriousness was largely necessity, "I was forced into designing furniture because I was designing offices and there was nothing suitable available"8, she recalled in a 1981 interview, expanding a couple years later with the reflection that, "I was never really a furniture designer, but designed furniture to fill in the gaps...."9

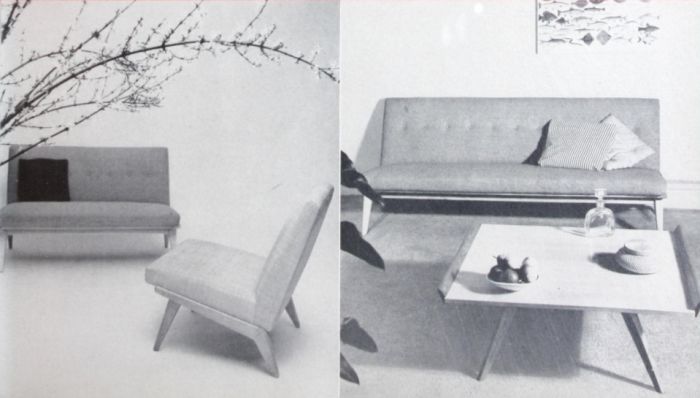

In 1957 Interiors magazine referred to Florence Knoll's furniture as "bread-and-butter"10 pieces, which sounds derogatory, but as phrase we really like it, summing up as it does not only the basic necessity from which the pieces arose, the gaps that needed filling, nor only their universality but also their unassuming self-assurance. There is nothing particularly outstanding about Florence Knoll's designs, they are in no sense the avant garde works that the likes of Saarinen or the Eames' were realising, nor the subtle, contemporary, reinterpretations of classic forms Edward J Wormley was developing for Dunbar, but they are neatly proportioned and well considered objects which bring a sense of comfort to the ideals of the inter-war functionalists, and which for all fulfil their intended function. And are largely objects which thanks to their universal self-assurance would fit very well in any contemporary domestic or office environment.

In 1955 Hans Knoll died in a car accident while on a business trip to Cuba, Florence took over the running of the business, and although she sold the brand in 1959 to Jamestown, New York, based manufacturer Art Metal Construction Company, continued to guide Knoll's fortunes as Design Director and Head of the Planning Unit until 1965 when she parted company with Knoll. Her last project being the interior design of Eero Saarinen's CBS Tower in New York, in effect bowing out where she had begun.

Her reasons for leaving were unquestionably many. In her letter of resignation she mentions "the responsibilities and interests of my private life in Miami"11, the city she had called home since marrying the banker Harry Hood Bassett in 1958, while in a later interview she states, "in a way I was bored. I worked so hard all my life, and I wasn't opposed to work; but really, when you've done 2,400 offices in the same building, it gets to be a bit much."12 One must also consider the changing nature of the American furniture market in the mid-1960s, for all the increasing number of competitors and tightening of budgets, and thus the shifting priorities of the brand's new, corporate, owners. It was arguably simply time.

What is without question is that her 22 years hard work helped establish Knoll as one of America's most important and innovative furniture manufacturers, or as George Nelson, who in his tenure as Design Director of Herman Miller was for many years Florence Knoll's only serious competitor, wrote in 1981, "Florence was the one who determined the standards of quality in both interiors and products, and there can be no doubt that her involvement in the firm was the crucial element in its eventual success."13

Having left Knoll Florence Knoll-Basett also left the spotlight and since 1965 has lived a low key, private, life in Miami where we trust she will celebrate her centenary in a suitable fashion.

Looking back on the early days Florence Knoll once told the New York Times, "Yes it was an exciting time, but it was mostly hard work. We had to battle the prejudice against contemporary design."14

Thank you that you did!

1Letter dated June 1st 1936, in Florence Knoll Bassett papers, 1932-2000. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Box 4, Folder 2: Letters (1930s-1940s)

2Florence Knoll Bassett papers, 1932-2000. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Series 1: Biographical Material, 1932-1999

3ibid

4"Equipment for living", Arts & Architecture, Los Angeles, May 1945

5Paul Makovsky, "Shu U.", Metropolis Magazine, July 2001 quoted in Phillip G. Hofstra, Florence Knoll, Design and the Modern American Office Workplace, PhD Thesis, University of Kansas, November 21st 2008

6Bobbye Tigerman, "'I Am Not a Decorator': Florence Knoll, the Knoll Planning Unit and the Making of the Modern Office", Journal of Design History, Vol. 20 No. 1 (Spring, 2007)

7ibid

8Jo Werne "She shaped Knoll into a major force in design", The Miami Herald, Sunday October 25 1981

9Joseph Giovannini "Florence Knoll: Form, not fashion" New York Times, April 7 1983

10Florence Knoll and the avant garde, Interiors, July 1957

11Letter dated January 14 1965, in Florence Knoll Bassett papers, 1932-2000. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Box 4, Folder 4: Letters (1960s)

12Maeve Slavin, "Florence Knoll: The making of the modern office", Working Woman, January 1984 in Florence Knoll Bassett papers, 1932-2000. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Box 2, Folder 2: Portfolio: Photographs of Florence Knoll and Others and Articles in Newspapers and Magazines, 1956-1997

13George Nelson, The age of modern design, Architectural Record, Mid-February 1982

14Joseph Giovannini "Florence Knoll: Form, not fashion" New York Times, April 7 1983

Happy Birthday Florence Knoll!