The German designer and silversmith Christian Dell is arguably best known for the numerous lighting designs he realised during the 1920s and 1930s.

Christian Dell was however also one of the pioneers of plastic design. If all too briefly.

Born in Offenbach am Main on February 24th 1893 Christian Dell initially completed a silversmith apprenticeship before studying at the Königlichen Zeichenakademie Hanau and subsequently serving as a journeyman silversmith, first in Dresden and then under Henry van de Velde at the Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstgewerbeschule in Weimar. Following a War and military service enforced career break, Christian Dell continued his journeyman career in München and Berlin, before completing his Master Studies in Hanau. In 1922 Christian Dell retuned to Weimar as Werkmeister in the metal workshop at Bauhaus, where along with the Formmeister László Moholy-Nagy and students such as, for example, Marianne Brandt, Hin Bredendieck, Wilhelm Wagenfeld or Carl Jacob Jucker, he played a key role in developing the Bauhaus understanding of and approach to product and lighting design.

When in 1925 Bauhaus was forced to relocate to Dessau Christian Dell chose instead a return to the River Main and the post of head of the metal workshop at the Kunsthochschule Frankfurt; an institution which at that time was being reorganised along much more industrial lines, and which, very much like Bauhaus Dessau, was looking to marry craft and industry. Parallel, Ernst May was developing his Neues Frankfurt urban planning project, one of the largest functionalist/modernist projects of the period, and one in which Christian Dell was closely involved - his lamp designs gracing not only the show houses of the various new estates but also the offices of numerous communal corporations.

Following the rise of the NSDAP Christian Dell, as an advocate of a modern, functional, anti-Germanic, approach to design, was relieved of his teaching duties at the Kunsthochschule. Declining numerous offers to emigrate to America Dell instead choose "internal exile" in Germany, working as a freelance designer - a period which saw the creation of his Idell collection for Gebr. Kaiser & Co., arguably Christian Dell's best known works. And sadly the only Christian Dell lamps still in production. Post war Christian Dell ran a silversmith and jewellery shop in Wiesbaden, from where, together with a local carpenter, he also developed the so-called "Dell-Mü-Uhren". Christian Dell died in Wiesbaden on July 18th 1974 aged 81.

The inter-war years were not only a period of formal and functional evolution in architecture and design, but also one of new materials, bent tubular steel and moulded plywood being the most obvious examples; however, the period also saw the rise of synthetic materials, the precursors of contemporary plastics.

In 1907 Leo Hendrik Baekeland filed his patent for Bakelite, the first fully synthetic resin and in many ways a material that has become synonymous for a whole class of phenolic resins, those synthetic materials which on account of their non-conductivity, heat resistance and ease of moulding made them ideal for the myriad modern electrical goods arriving on the market at that period.

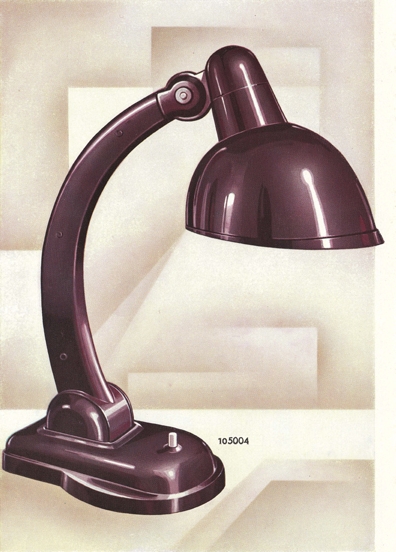

In 1908 Hermann Römmler filed a patent in Germany for the phenolic resin Hares, and through his company H. Römmler AG in Spremberg, Niederlausitz, began producing components for the electrical industry in first Hares and subsequently, and following the conclusion of a patent dispute, in Bakelite: as the only company in Germany with a commission free licence. An agreement which gave Römmler a huge advantage over their competitors, allowed them to quickly diversify and saw them move ever more from electrical components to consumer goods, including telephones, radio housings, car dashboards and in 1929 through a cooperation with the Frankfurt based lighting company Kontakt, the first desk lamp constructed entirely from a synthetic material - and a lamp designed by Christian Dell.

Or at least in all probability designed by Christian Dell, for as Dr Günter Lattermann excellently documents, while there is no direct link between the lamp and Dell, there is more than enough circumstantial evidence to make a very strong case for it being a Dell lamp. For us the most convincing being on the one hand the effortlessly simple functionality through the hinges at both base and lamp head which allow for free(ish) positioning with a minimum of technical complexity, while the form of the lamp head is unquestionably the shell like, parabolic, reflector of which, and as we've previously noted, Dell was so partial.

Revolutionary as these new phenolic resins were they had one serious drawback - they only came in varying shades of muddy brown.

The need for colour was obvious and came with the development of the so-called aminoplast resins.

In 1930 Römmler AG developed a new aminoplast resin which was premièred at the Leipzig Spring Fair as Alboresin before being renamed Resopal in 1931.

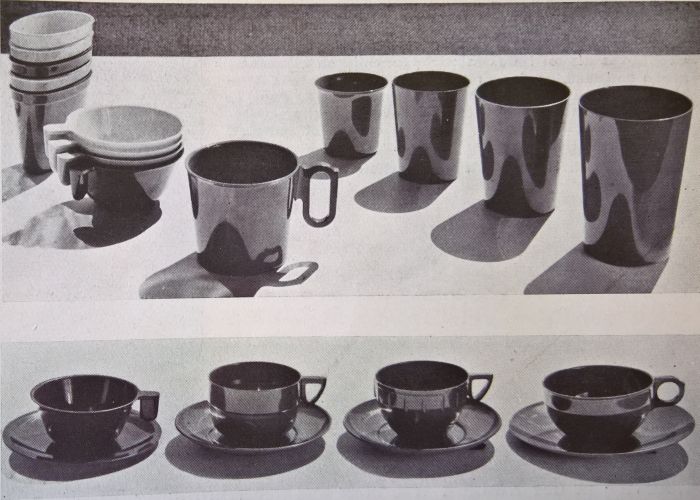

Whereas the origins of the "Pheonplast Lamp" are unclear, unequivocal is that Christian Dell created numerous Resopal objects for Römmler, largely plates, bowls, coffee sets, trays, serving dishes, egg cups, conserve containers ... so objects similar to those he would have created in metal. And similar not just in genre, but also formally. Viewing the works one can see not only direct reference to some of his earlier metal objects, but also elements of both his training and his understanding of design: with their paired down interpretation of neoclassic grandeur Dell's designs are very much of their age - and could just have easily been crafted in silver. Plastic however not only allowing for cheaper mass production, and that in a material much more suited to the new architecture and interior furnishings of the period, but also the realisation of the designs in vivid reds, yellows and greens. A plastic picnic set also neatly alluding to the social changes of the period which meant that ever more people had the time and opportunity to enjoy a picnic. It was no longer an exclusive pastime of the landed gentry.

Not that the temptation of the new material led Christian Dell to completely forget his roots: one collection of cups features ebony handles with silver mountings, a delightfully cheeky combination which today would no doubt be presented as juxtaposing cheap with valuable and thus posing questions of our understanding of both. We suspect Christian Dell just wanted to demonstrate both the equality of the materials and also the very real craftsmanship contained in the simple plastic cups. If you will, a bit of marketing for the new material.

While at the same time inventing the new profession of Plasticsmith.

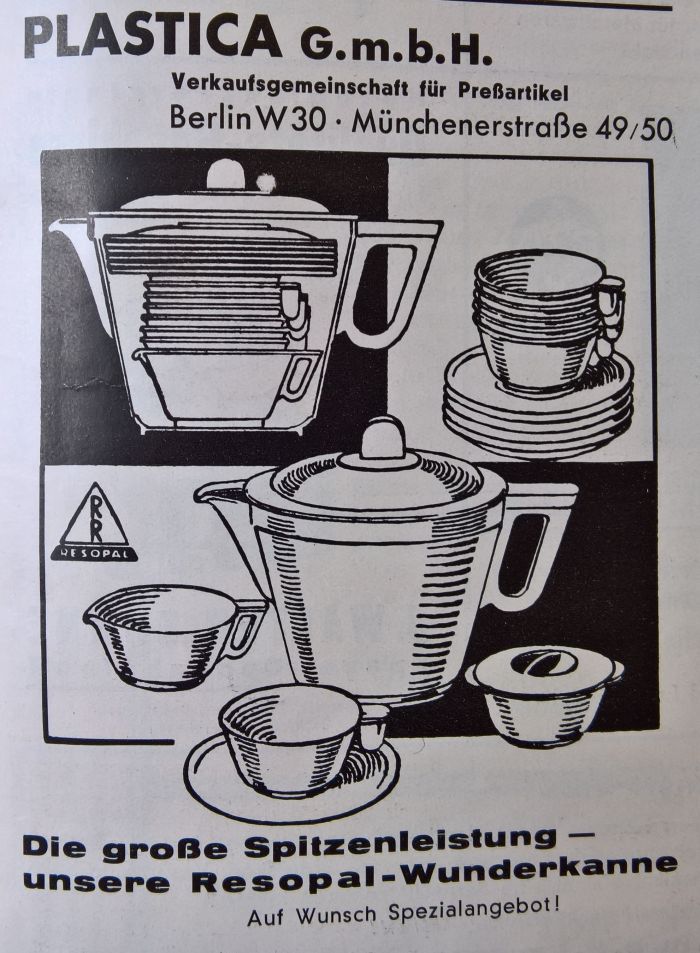

An important part of Christian Dell's Resopal service concepts was stackability, something perhaps most deliciously demonstrated by the so-called Sportservice in which 6 cups, 6 saucers plus sugar and cream bowls fit inside the coffee pot, a design referred to in the company's adverts, and with a fair amount of justification, as the Wunderkanne - Magic Coffee Pot. As we all learned from the exhibition Stapeln. Ein Prinzip der Moderne at the Wilhelm Wagenfeld Haus Bremen, stacking as a design principle largely arose from the development of new materials and processes which allowed the inter-war functionalists to develop standardised solutions. With his Resopal designs for Römmler Christian Dell was very much at the forefront of that development.

If only very, very briefly.

In the mid-1930s Römmler ceased production of household goods in Resopal and shifted their focus to the production of Resopal in sheets for use in construction and interiors, for all as kitchen and worktop surfaces; post-war not only did Christian Dell remove himself from industrial product design, but new generations of plastics appeared which allowed for much more durable objects, new production processes and ultimately the new forms that all new materials deserve, and thus the subsequent explosion of plastic as a material for furniture, furnishings and accessories.

Christian Dell's contribution to the development becoming in the process but a footnote. And not even that in the 1938 Römmler-Buch, which despite a very detailed history of company, products and processes finds no space for Christian Dell.

However, through the thoroughness of his design, the way he solved formal and production problems to realise objects which met the expected aesthetic and functional standards, and for all his intelligent marrying of a new material with new social, cultural and economic thinking to help solve contemporary problems, Christian Dell perfectly illustrated the possibilities inherent in the new synthetic materials, and thus helped pave the way for all that has come since.

Happy Birthday Christian Dell!