Whereas 3D printing is omnipresent in the media, and a ubiquitous tool in contemporary research and development, in most daily realities it remains scarcely present.

Save for tablet holders, cosplay accessories and Star Wars chess sets. Or put another way, as a popular activity 3D printing is still very nerd niche.

Often very, very trivial.

And certainly not a widespread, commercial, industrial process.

Yet.

But will be. Of that we are certain.

How that will be in context of the furniture industry is still very open, but with PrintStool, designer Thorsten Franck and manufacturer Wilkhahn have taken a very strong step in a very interesting direction.

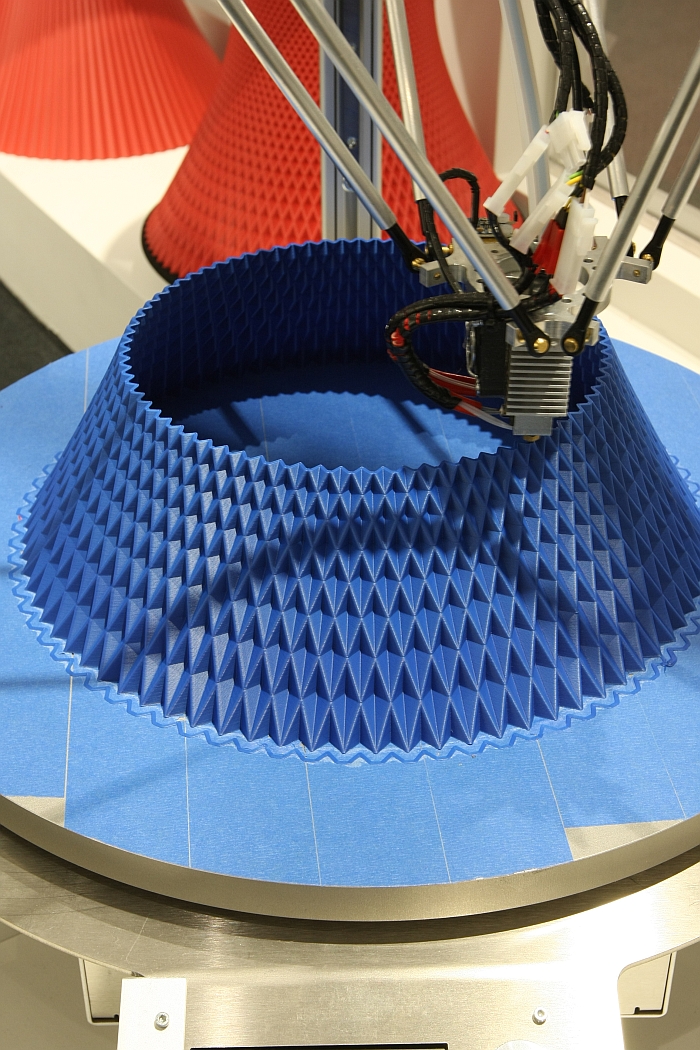

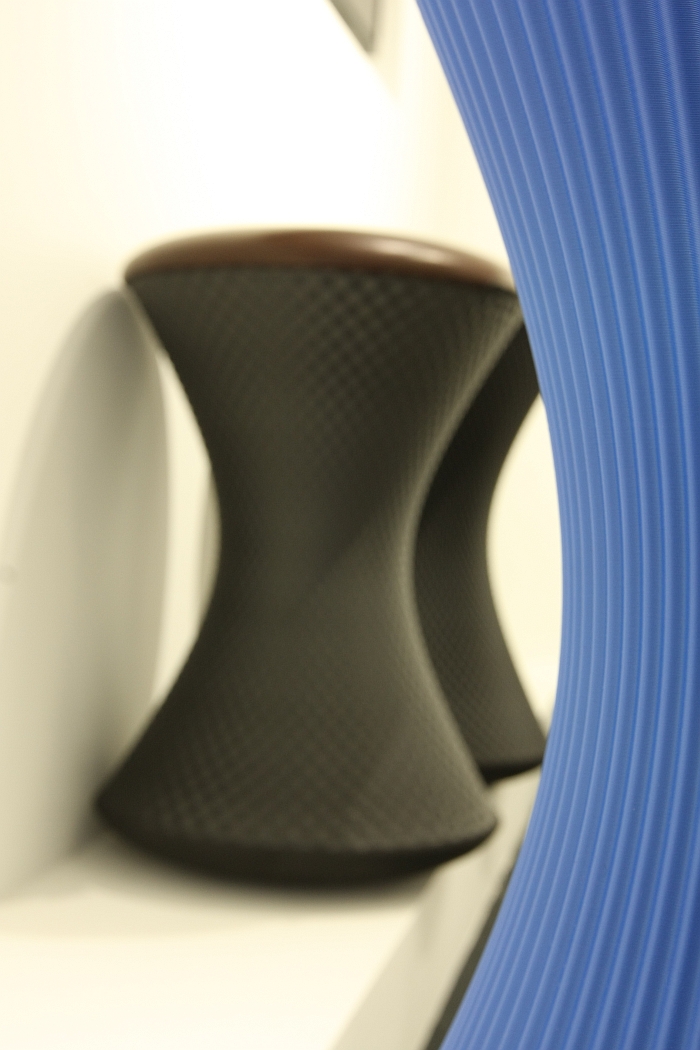

Initially presented at NeoCon Chicago 2016 PrintStool was introduced to the European public at Orgatec Cologne 2016 and is essentially nothing more complicated than a classic biconical, egg-timer, shaped stool. A classic egg-timer shaped stool available with a selection of geometric patterns and which thanks to the form of the base gently rocks with the user.

Not that there was anything random or unconsidered in the choice of such a classic shape. Far from it. "With its hyperboloid form it is a very stable structure", explains Thorsten Franck, "yet has a very small surface area which makes it excellent to print with a minimum of material."

Form follows function in the sense of the function being to be 3D printable. Not to be a stool.

Form follows function in the sense of the function of the exterior decoration being to increase the stability of the thin walled structure. Not to be decoration.

While the ability to realise the object with a minimum of material is an important component of Thorsten Franck's understanding of design. "Today when we have limited material availability we must use them more consciously, must consider new systems, new materials, and with 3D printing one has a completely new way of considering how objects can grow", continues Thorsten, "it is perhaps comparable to the philosophy of Frei Otto with his stretched, taught, surfaces, and working with dynamics rather than, for example, a material such as concrete."

And as with Frei Otto's constructions, realising the relatively logical, almost patently obvious, PrintStool involved a lot of research, experimentation and persuasion. External and internal.

"At the beginning everyone considered 3D printing such a stool impossible", says Thorsten Franck, "and to this day I don't know why I believed in it, not least because the initial attempts all failed!"

Undeterred Thorsten began a long process of development, a process of technical development, formal development and conceptual development: Thorsten being continually forced to consider and re-consider the fundamentals of 3D printing in an industrial context. "The first attempts were small and very fine, industry always wants products to be refined and perfect, but that causes a lot of problems with such a 3D printing process" he reflects, "and so I decided to make everything much coarser, we don't, for example, attempt to avoid the production traces, to make everything smooth and faultless, but rather accept that as an industrial process 3D printing also leaves traces of the production process. And that made everything a lot easier."

In addition came the fact that as Thorsten says, "when we started the software wasn't that far developed, the machines weren't particularly reliable, the materials weren't particularly stable, everything was still in development and that is all much more advanced now."

And so can one say that the idea was ready before the technology and material?

"It all developed together. Why should the technology develop when there is no material? And materials need an end use, a reason to exist."

The end use as presented in Chicago and Cologne being PrintStool, however for Thorsten Franck it is much more elementary, "in effect we have developed a system that allows, for example, a stool to be printed. But that could also be a table, a lamp or whatever one needs" he concludes.

A state of affairs with which Wilkhahn CEO Jochen Hahne concurs when we ask him what initially attracted him the project, and more importantly, what convinced him to take it on?

"It was the concept, not the stool itself, but the concept behind it. With the concept one can make almost anything, it could be such a stool, but needn't be", he answers, "at the time we first saw the project I was reading, amongst others, Jeremy Rifkin* and in a way everything came together, made perfect sense and I decided we had to do it."

As a process 3D printing isn't, and never can be, suitable for all furniture genres, or at least not in any future we'd want to be part of; however, in combination with open source technology and rapid production processes, for us must serve as a component of any future furniture industry.

Not least because a business model in which furniture is produced at location X before being distributed globally, be that to shops or direct to the end customer, is unsustainable in the long term. And perhaps more importantly, unjustifiable. We need new business models.

In which context one of the things that most excited us about the project when we first saw it in Chicago, and which continues to excite us, is the fact that for us it offers a realistic chance for decentralised production.

With streaming services the music industry has more or less been forced to move away from the physical object, with e-books the publishing industry has been a little more in control, but has still been forced to reconsider the physical object as the product. With furniture moving away from a physical object is a relative question, furniture will obviously remain physical, but needs to be produced with as little material input as possible, and for all needs to be produced as close as possible to the end user using locally sourced materials.

A business model based on the PrintStool concept allows just such. Not least because of the flexibility and adaptability inherent in the system

In conversation Thorsten Franck proposes various possibilities including producing objects on-site as a form of workshop, of involving, for example, office workers in the creation of their own furniture, or of centrally located technology houses, analogous to the communal bakehouses of yore, and where everyone can produce their own furniture. Jochen Hahne takes a much more furniture industry view, "we distribute worldwide, and for me the idea of, for example, reducing the delivery time to Australia from, roughly speaking, 12 weeks to 12 hours, is very alluring and exciting"

Or for us, and on a much more basic level: you stop off at your local furniture store on your way to work. Order such a stool in blue. With pattern X. They print it. You pick it up on the way home.

What's not to like?

As far as we are aware PrintStool is the first 3D printing project to be undertaken by a major producer. Much as we adore Dirk van der Kooij's work he remains a small, if successful and highly inventive and original, producer. And while Janne Kyttanen remains an influential and innovative designer, that wasn't enough to bring Freedom of Creation to a market relevant position. And among the major furniture producers......

If, and yes, PrintStool remains a goodly distance from being a market ready product. No-one should expect to find a PrintStool under their Christmas Tree this year. Thorsten Franck has demonstrated that 3D printing furniture is feasible, and now Wilkhahn have, in effect, the responsibility to transfer Thorsten's research into practical, daily industrial production. Something which is as much a question of legal, business, certification and market considerations, as it is of technical and work flow.

"We're still very much experimenting with the how and why", says Jochen Hahne "not least because the project involves topics and subjects with which we as a manufacturer normally aren't involved and which we first of all need to understand, also in terms of such a product's wider, market, acceptance. Rifkin said such technology would change the world, what he is much more vague on is when. But we definitely want to be involved when it does!"

And it will.

How that will be in context of the furniture industry is still very open, but with PrintStool, designer Thorsten Franck and manufacturer Wilkhahn have taken a very strong step in a very interesting direction, and one which leaves us more convinced than ever in a future with widespread, commercial, industrial, 3D furniture printing.

*American economist and author specialising in the impact of scientific and technological changes on economic and social realities. Leading proponent of the idea of The Third Industrial Revolution, a revolution fuelled by the internet and renewable energy.

PS. Normally we only use our photos from a fair or exhibition to illustrate objects seen at that fair or exhibition. It's important for us. However. Every time we visited the Wilkhahn stand at Orgatec 2016 the PrintStool examples were being presented to someone or were otherwise in use. And so we never got a chance. Over the course of three days. Which we understand as a positive state of affairs. And so in their place we have used our photos from NeoCon 2016. And the official Wilkhahn video.