If the (hi)story of 20th century architecture and design is unimaginable without the contribution made by Austria/Hungary/Austria-Hungary; then the contribution made by Austria/Hungary/Austria-Hungary is unimaginable without the contribution of Otto Wagner.

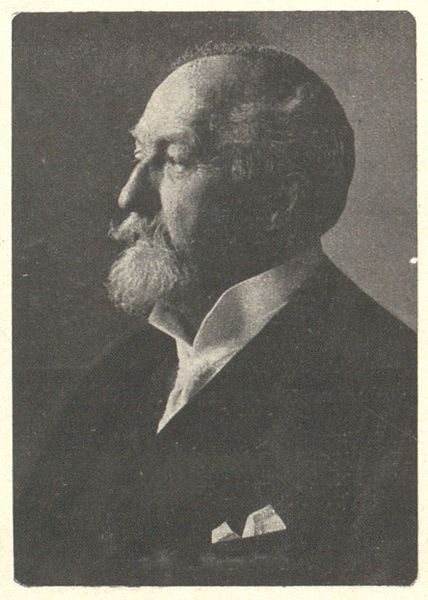

Born in Vienna on July 13th 1841 Otto Koloman Wagner studied first at the Wiener Polytechnikum and subsequently the Berliner Bauakademie, before returning to Vienna in 1861 and the Akademie der bildenden Künste. In 1864 Otto Wagner established his own architectural practice in Vienna, in which context he served as Site Manager for numerous projects realised in context of the Vienna Ringstrasse; not only one of the most important construction and urban development projects in the Vienna of that period, but a project representative of the city's vitality, prosperity and self-confidence. And a project which brought the young Otto Wagner into contact with many of the leading architects and political figures of the day.

As a freelance architect Otto Wagner initially realised numerous tenement blocks in Vienna, and whereas his early works were in the favoured Historicism style of the period, over the coming decades Otto Wagner increasingly freed himself from the dogmatic adherence to historic models and began to experiment with new forms and new methods of construction; describing, for example, in 1887 his project in Vienna's Stadiongasse Wagner notes, "The façade is kept simple, with all but a minimum of sculptural ornamentation, and rather a focus on expansive proportions, bigger windows and simple, clear motifs".1

And not only new forms and methods but also new ways of thinking about the function of architecture; an evolution perhaps best demonstrated by his 1893 competition entry for a new urban plan for Vienna. Aware of the contemporary social, cultural and political evolution, the increasing importance of technology and the associated changing nature of the urban fabric, Otto Wagner devised a city planned for new transport methods, for new communication methods, for ease of expansion, for the future. And a concept which clearly impressed the jury who awarded Wagner first prize, even if, and as so often with the winners of architecture competitions, the plan was never actually realised.

In 1894 Otto Wagner was commissioned to develop Vienna's new Stadtbahn urban railway network, and subsequently created an institution which remains one of the architectural highlights of the city, and in the same year was appointed Professor at his alma mater, the Akademie der bildenden Künste, where Wagner's position against historicism and classical architecture caused a fresh breeze to blow through the school's ateliers, a breeze which by 1901 had already led to talk of a "Wagner Schule"2 and that a school who's students included many of those who would go on to play important roles in the future development of international architecture and design, including Josef Hoffmann, Rudolph Schindler and Jože Plečnik.

And what they learned can be read in Otto Wagner's book "Moderne Architektur" - "Modern Architecture"

Published in 1896 Moderne Architektur was in many respects the first text to argue for new approaches to architecture, urban planning and construction; to argue for a greater cooperation between engineers and architects, the one responsible for the physical, the other for the artistic realisation; to argue for a practicality in architecture rather than a pure beauty; to argue for a simplicity of form devoid of the ornamentation and motifs of previous ages; to argue against the, until then, standard and blithely accepted, study tour of classical Italy undertaken by young architects and instead a call to visit the major European metropoli* in order to understand the needs of contemporary society; to argue for a modern architecture. And although against the backdrop of current understandings of architecture and design much of what Wagner wrote sounds almost embarrassingly obvious, in 1896 it was just short of revolutionary. Republished in 1898, 1902 and 1914 - the latter two versions with numerous changes and emendations over the first two - Moderne Architektur was not only one of the first outings for the term "modern architecture" but as a work existed during, and thus served as an important theoretical and ideological accompaniment to, a period of rapid change in architecture and design thinking: in Scotland Charles Rennie Mackintosh was translating Japanese aesthetics into Glaswegian sandstone; in France Siegfried Bing and Henry van de Velde were opening the "Salon d'Art Nouveau" in Paris; in Germany Großherzog Ernst Ludwig von Hessen was establishing the Mathildenhöhe artists colony in Darmstadt; in Finland Eliel Saarinen, Herman Gesellius and Armas Lindgren were struggling with the question of defining a contemporary Finnish national identity; while over in Chicago Louis H. Sullivan was confidently proclaiming "form ever follows function, and this is the law."

As with Louis H. Sullivan the basis for Otto Wagner's new thinking was on the one hand the new types of buildings that were needed for the contemporary city, and on the other the opportunities afforded by new materials and new construction methods. Unlike Chicago Vienna wasn't busily building skyscrapers, but, for example, in realising his ever genial Postsparkasse Otto Wagner employed, as arguably one of the first in Central Europe, steel reinforced concrete, while the monumental glass roof over the main banking hall not only makes no effort to hide its underlying construction principle, but positively celebrates it: it is we suspect no coincidence that Postsparkasse remains one of the most splendid and compelling buildings in the Austrian capital. Or indeed any city.

In addition to architecture and urban planning Otto Wagner was also an active member of the pre-Jugendstil Wiener Secession, and in demand as an interior and furniture designer, in which context we refer the interested reader to the interior of the Postsparkasse, a work which is not only an excellent definition of the term Gesamtkunstwerk, but whose furniture presents a refined, if luxurious, simplicity every bit as delicious as the architecture.

Otto Wagner officially retired from his Professorship at the Akademie der bildenden Künste in 1912, remained however on the teaching staff until 1915, by which time the realities of the First World War overshadowed all other enterprises. Otto Wagner died in Vienna on April 11th 1918, and while the man was gone his spirit remained in the work of those students he had inspired, and who were in the process of reforming architecture and design and thus were themselves inspiring the next generation of architects and designers.

Happy Birthday Otto Wagner!

* as ever, we know "metropoli" isn't the plural of metropolis. Passionately believe it should be

1Otto Wagner, "Wohnhaus, I., Stadiongasse 6 und 8 in Wien" Allgemeine Bauzeitung, Wien, 1887 http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno-plus?aid=abz&datum=1887&page=61&size=45 Accessed 12.07.2016

2Wagner Schule 01, Der Architekt - Supplemente 7, Wien, 1901 http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno-plus?aid=ars&datum=0007 Accessed 12.07.2016