As with contemporary football the story of contemporary architecture and design begins on the British Isles; and as with football it didn't take long before the British nations were replaced at the forefront of the art(s) by their European neighbours. In both cases Germany and France moving with notable speed, diligence and grace past the UK.

Inspired by this coming summer's EURO 2016 European Football Championships in France, the Bröhan Museum Berlin are celebrating the creative rivalry which existed between France and Germany in the first decades of the 20th century.

“Following the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 and 1871 politics in Europe was largely dominated and defined by the relationship between Germany and France, and this also rubbed of on to cultural questions, the two nations saw themselves as the most important, and in the other the principle rival”, explains Bröhan Museum Director and exhibition curator Dr. Tobias Hoffmann, the background to the exhibition, “and from 1900 to 1930 the relationship between France and Germany was particularly intense, was in many ways the most important relationship in terms of European creativity, and with this exhibition we want to investigate the nature of that relationship.”

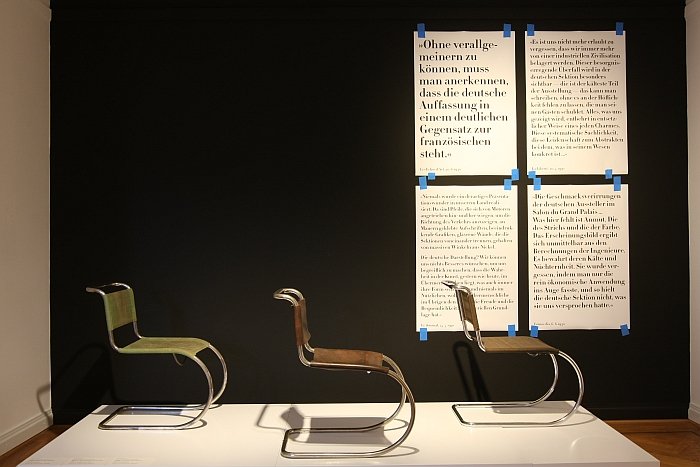

To this end the Bröhan Museum are presenting some 300 objects in a, largely, chronological exhibition which, and as with all good football matches, is a visually pleasing spectacle, a game of two halves and a contest defined by a few key moments, “In effect France shoot the 1:0 with the pompous Art Nouveau”, comments Dr Hoffmann; although in many respects the goal must considered more a deflection from a German than a French goal per se: the name Art Nouveau famously coming from the Salon d’Art Nouveau opened in Paris in December 1895 by the Hamburg born art dealer and collector Siegfried Bing. And although Bing did later acquire French citizenship, at that moment he was very definitely a German citizen.

Over the following years the Germans kept up the pressure on France, appearing on several occasions to have found a way through the more decorative aspects of Art Nouveau and thus achieve the equaliser, before a swift counter attack, and one in our opinion largely enabled by squabbling in the German midfield about the importance of normative forms against artistic freedom, saw the French move into a 2:0 lead thanks to Art Deco: a movement whose origins are French but which in many respects, if only allegedly, owes its name the Swiss architect and designer Le Corbusier.

A state of affairs which neatly demonstrates that even in the closely confined arena of a museum exhibition it is impossible to maintain that the period witnessed a purely Franco-Teutonic contest; foreign, naturalised, players featured heavily in both teams, and are thus logically featured in the exhibition, including amongst others, the aforementioned Le Corbusier, the Austrian architect Joseph Maria Olbrich who played a key role in the development of the Darmstadt Artists’ Colony, the Magyar Marcel Breuer, the Netherlander Gerrit T. Rietveld or the legendary Belgian centre forward Henry van de Velde, who was not only part of Art Nouveau’s christening and thus involved in the 1:0 for France, but later would contribute to helping the Germans find a way back into the match.

Against this strong line-up of international talent, the question does naturally arise as to the role of Berlin, given that the match is being staged in Berlin, does Berlin play an important role on the pitch?

“Very much so”, answers Tobias Hoffmann, “for a long time Berlin lag a long way behind Paris, which had established itself in the 19th century as one of the grandest metropolises in Europe and Berlin only started to catch up following the establishment of the German Reich in 1871. Berlin however is the place where the committed, commercially orientated, cooperation with industry, so functionalist design, achieves its breakthrough.”

And the subsequent narrowing of the gap to 2:1 through the development of such close cooperations between industry and the creative arts, as perhaps best demonstrated by Peter Behrens’ architecture, product design, graphic design, interior design and garden design work for AEG, but also through contributions from the likes of Bruno Paul or Richard Riemerschmid.

The importance of the period immediately before the First World War, and the shift it marks in the relationship between France and Germany can be seen by the fact that in 1910 the Art School in the Swiss city La-Chaux-de-Fonds dispatched their then student Charles-Édouard Jeanneret a.k.a Le Corbusier on a study tour of Germany to investigate contemporary architecture and applied arts: They wanted to know what the Germans were doing, and learn from that. The resulting 1912 publication A Study of the Decorative Art Movement in Germany, not only providing the first documentation of what was being undertaken in Germany at that period, and serving as a source of inspiration for designers and architects throughout Europe, including Le Corbusier, but also unequivocally confirming that a new age was waiting to substituted onto the field of play.

A new age which played its most defining and most intensive role in the years after the First World War with the rise of Functionalism, a movement given arguably its best, most expressive and for all most dominant voice in Germany with institutions such as Bauhaus Dessau, exhibitions such as Weissenhofsiedlung Stuttgart or programmes such as Neue Frankfurt, and thus marking the 2:2.

And the final whistle.

A fair result, and for all a fair contest?

“During the match it did occasionally get quite heated, but at the end it was more harmonious, and by 1930 we have a very balanced and even relationship. And perhaps best of all is the fact that by the end of the match it had evolved into a friendly, where the designers had realised that it made little sense to work against one another”, reflects Tobias Hoffmann in his post-match analysis.

In addition to explaining the interactions and shifts in power in the Franco-German cultural relationship of the period, Germany versus France also very neatly explains that the path from 1900 to 1930, and so in effect from Art Nouveau over Art Deco to Functionalism, was a continuous process. As we noted in our post from the exhibition Art Déco: Smart, Precious, Sensual at the Grassi Museum Leipzig, terms such as Art Nouveau, Art Deco or Functionalism, can be counter productive, can confuse and lead one to think in terms of rigidly defined compartments. You can't. And certainly shouldn't. Walking through Germany versus France this becomes beautifully clear. There are no clearly defined transitions, it is one uninterrupted progression.

Complimenting the furniture and applied art works Germany versus France also presents examples of poster design, painting and sculpture from the period and backs up the displayed works with photos and videos. One particularly nice moment is the comparison between the Paris and Berlin underground systems: the period in question being exactly that when the suburban railway systems were being established and creating networks which are still largely dominated by the styles of then, and which thus form a persisting link between the early 20th century and today.

A particularly intelligent contribution to the exhibition is made by the large number of quotes from leading protagonists which adorn the walls of the exhibition rooms like the deliberations of TV football pundits. Just more meaningful, considered and intelligent. And quotes which either/or/both set the neighbouring objects in context or allow visitors to understand the exhibition and the exhibits in their wider context. An effect ably supported by the short texts which introduce the 20 sections into which the exhibition is split.

Viewing Germany versus France it is unavoidable to ask how such a contest would end today. Assuming, as we are, that Konstantin Grcic and Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec served as team captains, a continuation of the friendly state of affairs from 1930 would continue: both have their own projects, their own approach to and understanding of design, but also together form the corner flags, sorry stones, of numerous international manufacturers' portfolios, including, Vitra, Magis or Mattiazzi, and thus they cooperate as much as they compete. Behind the captains you would have to say that Germany currently have the better depth of experienced contemporary talent, and for all the better youth development programmes, and thus the better long term prospects. A state of affairs indicated, when not predicted, by Germany versus France in the observation that whereas from the early 1900s onwards Germany invested in the establishment and development of art and design schools, France didn't. And largely still doesn't.

A very classic, museal presentation of the subject matter, Germany versus France is a very accessible, easy to follow, clearly laid out and uncluttered, unhurried exhibition which not only competently explains some of the major moments of the period, but which through the intelligent juxtaposition of objects and protagonists also allows for simple comparisons which often explain more than any text could.

The (hi)story of European architecture and design from 1900-1930 is of course not just one of France and Germany, and the Bröhan Museum certainly aren't claiming it is, but in reducing the exploration of the period down to two countries one creates an eminently understandable exhibition which allows the visitor to enjoy the spectacle without becoming unnecessarily bogged down in details, philosophies or the offside rule.

And what does Tobias Hoffmann hope the visitors take with them from the exhibition? "That they understand just how much the two nations profited from one another, that for long periods Germany and France couldn't live with or without the other, that they were dependent on one another, and that an awareness of this is something that we need in Europe today more than ever."

We seriously doubt the football tournament will achieve that, the Bröhan Museum's exhibition might just.

Germany versus France. The Struggle over Style 1900-1930 runs at the Bröhan Museum, Schloßstraße 1a, 14059 Berlin until Sunday September 11th

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at: www.broehan-museum.de