Clearly vexed by a critical review in Architectural Forum of his friend Alexander Girard's Santa Fe house, Charles Eames wrote a short letter on December 26th 1956 to the magazine's editor Walter McQuade:

"Alexander Girard is interested in the quality of everything and does not hesitate to act on this interest, personally and immediately. Such action could not possibly result in a cliche; and not being cliche demands an explanation.

The answer perhaps is in Girard's total involvement in things he touches, allowing no time barriers. Also of some significance is the fact that he is part Magpie - and a Florentine one at that"

Alexander Girard's interest in quality, total involvement and his magpie-esque tendencies can be explored in the Vitra Design Museum's exhibition Alexander Girard. A Designer's Universe.

Born 1907 in New York City as the son of an American mother and a French/Italian father Alexander Girard was raised in Florence before in 1917 he was enrolled in the Bedford Modern boarding school in London, a city in which he subsequently studied architecture at the Architectural Association, graduating in 1929. In 1932, and after stations in Stockholm and Rome, Alexander Girard "returned" to New York where he designed furniture and interiors for private customer before in 1937 he, and his new wife Susan, moved to Detroit where he began working for a local interior design studio. And where fate in her fickle way had more in hand for him....

In 1943 Alexander Girard re-designed the canteen for Detroit radio manufacturer Detrola, whose chief designer he became in 1945. Legend has it that one day Charles Eames, who at that time was working with the Evans Products Company in Los Angeles and was involved with designing moulded plywood radio cases, arrived at Detrola to tout for business. Alexander Girard was not at his desk and so Eames left a note to the effect that he had been, and could see that Detrola didn't need him, the chief designer they currently had was obviously much better. Apocryphal as that may or may not be, what is certain is that having moved to Detroit Girard developed deep and long friendships with many of the leading figures of the near-by Cranbrook Academy of Art, including Charles & Ray Eames and Eero Saarinen, with whom he first co-operated in 1948, before in 1951 George Nelson appointed Alexander Girard as head of the textiles department of the Herman Miller furniture company, in which role he created more than 300 textile designs, helped define the look and feel of numerous Herman Miller domestic and office furniture programmes, and which was to become the role for which he is unquestionably best known.

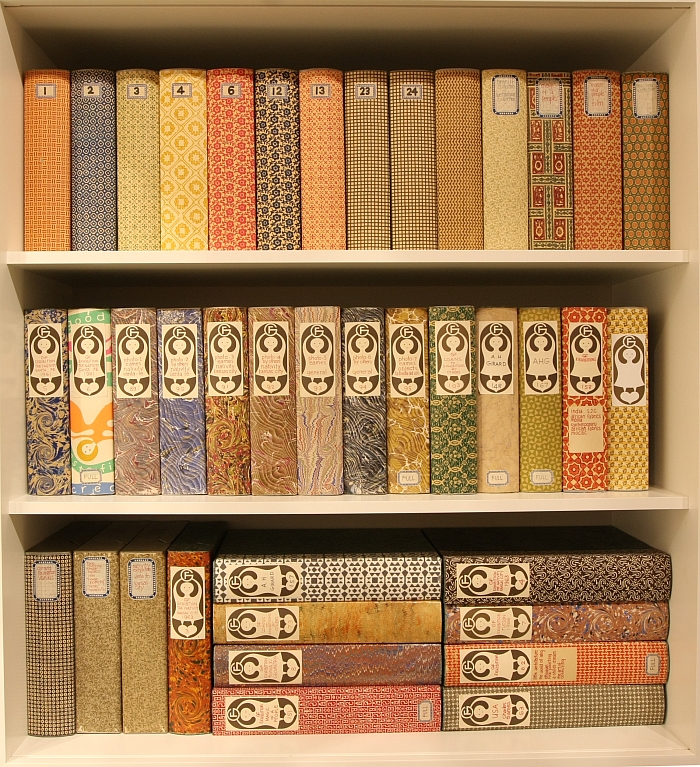

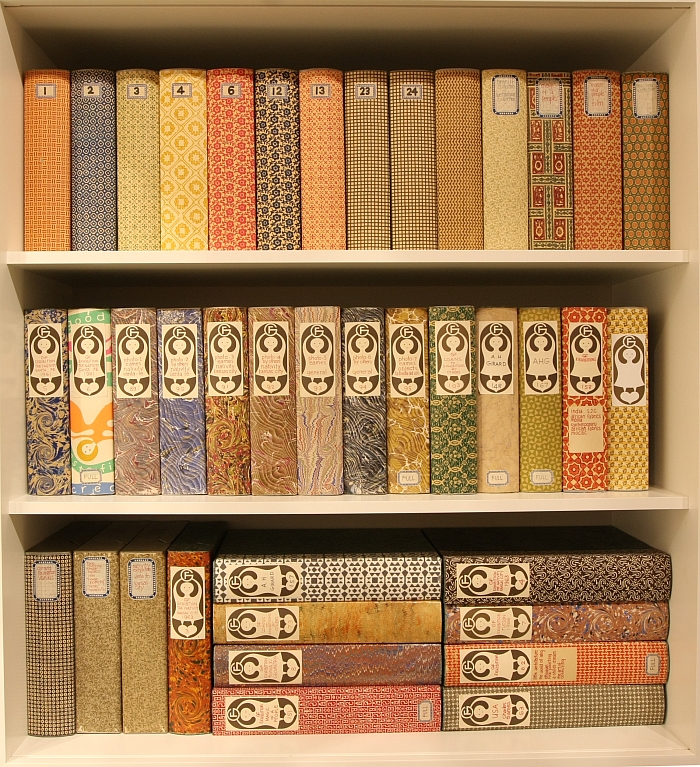

In addition to his co-operations with Herman Miller Alexander Girard was also a successful and much requested exhibition designer, a successful and much requested interior designer, a less requested, less successful if, in our opinion, very highly talented, furniture designer - his so-called "Girard Group" from 1967 for Herman Miller being one of the motivations for our Lost Furniture Design Classics series - he designed cutlery, tableware and household goods, created an entire corporate identity for Braniff Airlines, and, and possibly above everything else, Alexander Girard collected folk art, and collected folk art, and collected folk art, and.... In 1978 when he donated his collection to the State of New Mexico it encompassed over 100,000 items.

As Charles Eames correctly identified, "he is part Magpie"; and this passion for collecting in many ways helped form his understanding of the world and defined how he approached his work and understood both his function and the function of those objects and environments he created.

Alexander Girard died in 1993 aged 85 and in 1996 his personal archive was entrusted to the Vitra Design Museum, A Designer's Universe is the result of the first structured, scientific study of that archive.

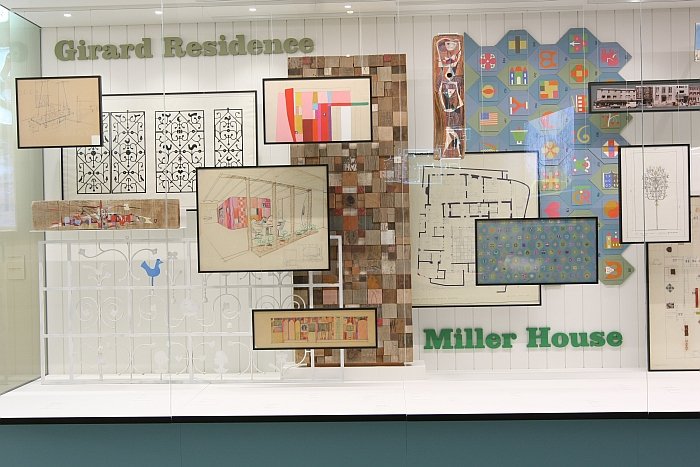

Curated by the Vitra Design Museum's Chief Curator, Dr Jochen Eisenbrand, and set in an exhibition design concept by London based studio Raw Edges, A Designer's Universe opens with an excellent introduction to Alexander Girard's early years, an introduction which includes not only many previously unseen/rarely seen works but also new biographical details, before moving on to look in more detail at aspects of his work. His extensive textile design work is given its own room, staged in a fashion akin to the 1975 Girard curated exhibition "The Design Process at Herman Miller"; his corporate design work explored through his cooperation with Braniff Airlines; restaurant design projects such as La Fonda del Sol and L'Etoile in New York are presented with displays of objects and furniture Girard created as well as photos from the original interiors; his further interior design work explained via plans, objects and photos from and of some of his key projects, including the so-called Miller House developed in conjunction with Eero Saarinen and which saw Girard create a seating pit for the living room: a seating pit which is recreated in the heart of the ground floor exhibition space. Upstairs the main focus is Girard's exhibition design work and a representative presentation of his folk art collection. Assuming that is one can "represent" a collection of over 100,000 objects.

And assuming that is one can genuinely "represent" a designer who over so many years was active in so many fields and responsible for so many projects.

Given the scale and diversity of the subject matter, an exhibition such as A Designer's Universe can never more than scratch the surface, provide an honest and factual, if necessarily shallow portrayal of the story it is telling.

And given the nature of the majority of the objects included, an exhibition such as A Designer's Universe inevitably features an awful lot of objects in display cabinets. Which is never, ever, a good exhibition concept. Ever. And especially not in context of an exhibition about a man who once said, "To me, nothing could be worse than an exhibition in which a number of objects are just lined up in cases"

But.

Given the age, materials, and for all, the size of the majority of the objects included, what other choice did the organisers have? And so no its not ideal, but the exhibits have to be presented in a meaningful context, and in meaningful relationships, and sometimes that means glass cases. And it is not just objects lined up in glass cases, for all the first room with the biographical information and the second with the textiles contain a few very well conceived and realised display solutions.

And so yes, it was nasty, unkind and a little uncouth of us to bring up the Girard quote. If also important.

Equally important is to remember that Girard also once said, "Part of my passion has always been to see objects in context. I believe that if you put objects into a world which is ostensibly their own, the whole thing begins to breathe. It’s creating a slice of life in a way. Then the exhibit becomes alive."

And if we agree to understand the "context" here as being less the objects per se and more about them helping explain the person Alexander Girard to a public largely, or in many cases completely, unfamiliar with the man and his work, then the objects are in a world ostensibly their own, a world, or perhaps better put a universe, of Alexander Girard's making and thus despite the glass cabinets the exhibition does breath.

Something it does all the more easily thanks to the amount of space Raw Edges have managed to create for the exhibition in the famously restricted space of the Vitra Design Museum. In the past we have often commented negatively about the limitations of the Gehry building for staging exhibitions of the scale the Vitra Design Museum realise; with Alexander Girard A Designer's Universe the exhibition design leaves a lot of space, for both movement and reflection, and that although featuring as it does some 700 objects it is twice as large as a "normal" exhibition.

Given the problems of finding an appropriate method of displaying many of the objects, for all the folk art, walking round the exhibition we found our thoughts continually returning to Alexander Girard's home in Santa Fe, a location we have long imagined as a veritable curiosity shop of objects from across geography and time, organised in the charmingly disorganised manner of the obsessed. But was it, or.......?

"His home was incredibly well organised", answers Aleishall Girard Maxon, granddaughter of Alexander Girard, and thus shattering one of our dearest held visions, "there were certain pieces that were key to the house, occasionally even built into the architecture, and then other pieces that would come and go because he had so many pieces he loved and he was thus continually changing the curation"

And thus instantly presenting us with an equally endearing impression. Which means, we ask, cautiously, the collection was always close at hand?

"It was in a specially built store room adjacent to his house, which also contained a processing room for all the folk art that was continually arriving, and it was all connected so you could walk from the store room to the kitchen in two minutes" continues Aleishall, "and in many ways that was an integral part of how he was able to do as many things he did, the fact that he created a space to facilitate his interest"

Alexander Girard often talks about folk art as a connection to the innocence of childhood and how through folk art we are reminded of life's essential wonder, were you as children also allowed to play with the objects?

"Some of them yes" replies Kori Girard, brother of Aleishall, "he would create a small cubby* where we could go and all the stuff there was hands on, and the rest we were allowed to explore but not touch"

And viewing the exhibition can they identify their grandfather in the show, is he present?

"Definitely" replies Kori, "one of the powerful things about his work is that it is representative of him in so many ways. You can isolate one piece and it would identify him, and here where you have so many pieces it definitely reflects the many different disciplines he worked in, the experiments he undertook and for all the varied passions he had."

Despite these numerous passions, the many strings to Alexander Girard's bow, the number of projects on which he worked, the stature of those with whom he cooperated, and the company he kept, the Universe as it were to which the exhibition title refers, Alexander Girard remains one of the lesser known and lesser understood designers of what is understood today as mid-century American modernism, but does this lack of recognition also underplay his importance, for all in context of the success of Herman Miller in the 1950s and 1960s and thus the rise of American design in that period?

"I think so, yes", answers exhibition curator Jochen Eisenbrand, "the Eameses were important for furniture, George Nelson as Design Director for the overall direction, the advertising and identity, and then Alexander Girard was important for the textiles and the colours, an area which is regularly overlooked but which plays an essential role in how the objects were received and their ultimate success"

Particularly we presume in context of the period, of post-War America and the changes in understandings of and demands from domestic furnishings.....

"Indeed, and Girard was partly responsible for propagating that shift. In the 1930s and 40s America looked very much towards Europe in terms of design and interiors, after the war America took up the lead itself and an Alexander Girard was one of those who took ideas from Europe and attempted to give the cooler, glass and steel tube designs a more human touch"

But was he happy with this role, as it were, next to but somehow also behind the likes of Eames or Nelson?

"I don't think today anyone can say for certain", replies Vitra Design Museum Director Mateo Kries, "but he knew that his great strength was not in designing the single object but rather creating the framework, the space, the interior. And then he was smart enough to understand that people like Charles Eames or Eero Saarinen had designed great furniture, and he had the talent to use them, to place them in his interiors and to combine them with textiles from Morocco, cushions from Afghanistan, to create a fitting colour scheme for and around them and also to communicate the designs in an exhibition, which was another of his great strengths. Alexander Girard was always thinking more about systems than the single object, Alexander Girard connected things, he connected ideas, connected people."

A Designer's Universe neatly explains how these connections worked, how Alexander Girard fits into the history of design and why it is dangerous to pigeon-hole creatives - and particularly dangerous to pigeon-hole a Florentine magpie.

At the exhibition opening there were a couple of mentions to that fact that whereas with Charles and Ray Eames or George Nelson one is always looking for a new angle, a previously un- or under- explored facet, with Alexander Girard his relative obscurity means such is not a problem, Alexander Girard is the subject, and A Designer's Universe is an excellent introduction to the man, his work and his place in the development of contemporary design, but what can today's designers learn from an Alexander Girard?

"For all that it can make a lot of sense to collect", answers Jochen Eisenbrand, "to establish a visual archive as a source of, potential, inspiration, but also one can learn a lot about the use of colour and that one shouldn't be afraid of ornamentation and decoration, such has its place, one must have the ability and understanding to use it correctly, but such can have a positive value"

And the rest of us, what do Aleishall and Kori hope visitors learn from the exhibition, from their grandfather?

"I hope that visitors take home with them the inspiration to lead a more creative, integrative and a more accepting life" answer Kori Girard, "and to understand that inspiration can come from so many places." "Through his work", continues Aleishall, "he asked the viewer to think for themselves, to recognise that anyone can create and have a creative life and I feel like his work was often based on pursuing that idea"

Which also sounds like the perfect "P.S." to Charles Eames' 1956 letter......

Alexander Girard A Designer's Universe runs at the Vitra Design Museum, Charles-Eames-Str. 2, 79576 Weil am Rhein until Sunday January 29th 2017

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at www.design-museum.de

*cubby = cubby hole, den, retreat