In his Letter of Reference for Christian Dell on the occasion of his departure from the Kunsthochschule Frankfurt, the school's Director Fritz Wichert wrote: "...highly distinguished as college lecturer, silversmith and as an inventor and designer for the lighting industry. His technical ability, his sense for structure and the beauty of materials and his noble, uncluttered forms make him in my opinion the leading figure in this field in Germany."

A perfect demonstration of what Fritz Wichert meant can be observed in Christian Dell's Rondella Lamp from 1926, one of his earliest designs, and a design which, despite being 90 years old, still has a lot to teach contemporary lighting designers. Or could......

Born in Offenbach am Main in 1893 as the son of a locksmith, Christian Dell initially trained as a silversmith before enrolling in first the Königlichen Zeichenakademie Hanau and subsequently the Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstgewerbeschule in Weimar where he was a student of Henry van de Velde. Following the first World War and military service Christian Dell briefly ran his own silversmith workshop in Hanau before in 1922 he enrolled in Bauhaus Weimar. Initially concerned with classic silversmith objects, from 1923 onwards Christian Dell was increasingly involved in and with Bauhaus lighting design projects, most notably helping develop the various lamp designs for the 1923 Haus Am Horn project in cooperation with Georg Muche, László Moholy-Nagy and Carl Jacob Jucker. Following the closure of Bauhaus Weimar Christian Dell returned to the River Main and Frankfurt where on February 1st 1926 he took up a position as head of the metal workshop at the Kunsthochschule Frankfurt. A position which was principally concerned with lamp design, and for all developing lamps for serial production.

According to Beate Alice Hofmann Christian Dell's focus on lamp design work in Frankfurt can be understood against the background of the Kulturpolitik of the then Frankfurt Mayor Ludwig Landmann and the closely associated Neue Frankfurt housing and urban planning projects led by city architect Ernst May. Elected in 1924 Ludwig Landmann sought, according to Nicholas Bullock, to "revive the great tradition of the city in the years before 1866 when Frankfurt had been a free city" and to make Frankfurt "an example of what the modern city could offer to the twentieth century, providing fully for the growth of an urban culture which would lead "men of art and science" forward in their search for the spirit of the New Age."

A central role in this was to played by Ernst May and Neue Frankfurt as well as by a re-organisation of the teaching at the Frankfurt Kunsthochschule to allow for a greater concentration on the unification of craft and industry; all very "Bauhaus" and indeed following the decision by the authorities in Weimar to cease funding Bauhaus negotiations took place between Walter Groupius and the Kunsthochschule's Director Fritz Wichert to investigate bringing Bauhaus to Frankfurt. That an agreement couldn't be reached Wichert set about transforming the Frankfurt Kunsthochschule, including the hiring of several former Bauhäusler to fill key positions, and bring a bit of the Bauhaus ethos and experience to Frankfurt; Adolf Meyer for example being installed as head of the architecture department, and Christian Dell of the metal workshop.

That the metal workshop in Frankfurt concentrated principally on lighting can be understood in context of the period. The ever wider availability of mains electricity and rapidly improving light bulb technology opened up new options for domestic, factory and office lighting; new options which neatly complimented and augmented the architectural and interior design philosophies of the day, and the leading protagonists' aims of developing affordable, durable, healthy environments in which to live and work. The Dane Poul Henningsen, for example, enjoyed pan-European success with his PH lamps while the metal workshop at Bauhaus Dessau was also very active in terms of lighting designs, for all through their cooperations with the Leipzig based manufacturer Kandem, a cooperation in context of which Marianne Brandt, Hin Bredendieck and Heinrich Siegfried Bormann were particularly active. Thus it is little wonder that an institution such as the Kunsthochschule in a city such as late 1920s Frankfurt should also focus on lighting design.

Christian Dell's first Frankfurt lamp project was the co-called Bürgermeisterlampe, a desk lamp created in 1926 for Oberbürgermeister Landmann. A, thankfully, one off piece the Bürgermeisterlampe is a dangerously art deco affair crafted from metal, silver, glass and enamel; does however formally set the tone for the Rondella lamp from the same year.

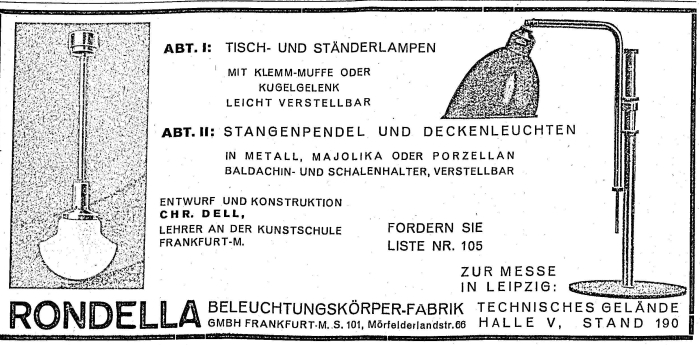

Presenting itself, epoch-appropriate, in a reduced, linear guise the Rondella lamp was available in a floor or a table format, the table lamp coming in a "simple" or a "better" version; the former crafted from an aluminium reflector and iron base, the "better" version featuring both in copper.

The defining feature of the Rondella lamp is the sleeve clamp, the Klemmmuffe, a device which enables the lamp reflector to be effortlessly moved and subsequently fixed in position, or as the industry magazine "Licht und Lampe" noted, "A light nudge up, down or sideways is enough to bring the spotlight-like reflector to where the light is required. Troublesome tightening of screws is avoided thanks to the unique construction of the sleeve clamp which automatically binds fast." Albeit not 100% automatically, a little bit of manual input is required, but minimal and effortless. And we think we can forgive the collegues at Licht und Lampe for getting carried away. Unquestionably a silversmith's solution to a technical challenge the Klemmmuffe is as unobtrusive as it is functional, as self-evident as it is elegant. And a text book example of the unifying of craft and industry that was at the heart of so much of the philosophy of the modernist era, and of the Kunsthochschule Frankfurt.

For us the genuine joy of the lamp however is that the reflector rotates around the central axis, an astonishingly simple functionality but one that it is very difficult to arrive at. And again for us there is something of the silversmith in the solution, of working with the materials one has without adding anything unnecessary. Or put another way, whereas others were, and still are, developing lamps with technical articulated arm mechanisms, silversmith Dell took what was there and created from it a functional feature.

We are, to be honest, less sure about the shell like, parabolic form of the reflector, but Christian Dell was obviously very impressed and repeated it, if occasionally in lightly adapted form, in most of his subsequent lamp designs.

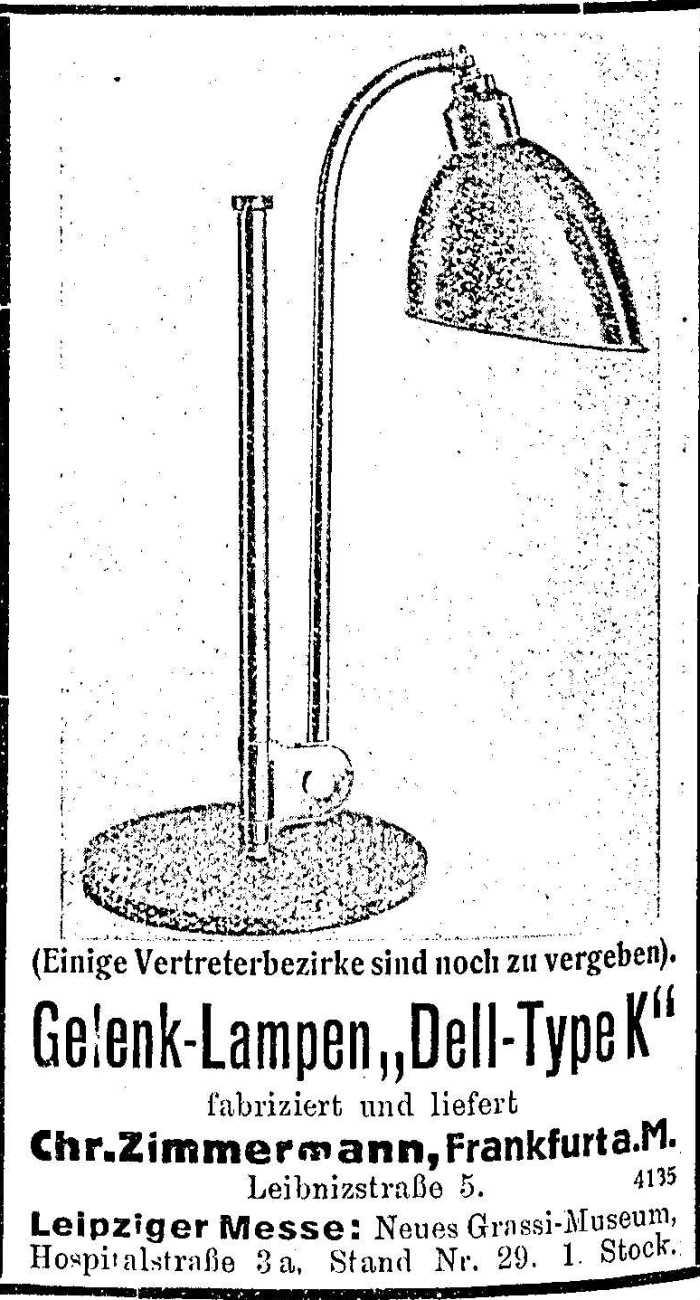

Following on from the Rondella floor and table lamps Christian Dell created a whole family of Rondellas including the so-called Rondella Polo which featured a ball joint connection between supporting arm and base and which allowed the lamp to be both pitched and swivelled, thus adding a degree more mobility than that found in the Rondella. A later lamp family, the Dell-Lamp Type K produced by Frankfurt based Zimmermann GmbH, combines various elements of the Rondellas in a collection of lamps which may be neat dictionary definitions of functional, but which for us lack the grace and sophistication of the Rondella.

In 1933 Christian Dell and his progressive colleagues were relieved of their teaching duties by the much less progressive NSDAP, whereupon Christian Dell became a freelance designer and among other commissions developed lamps for the manufacturer Gebr. Kaiser & Co. in Neheim-Hüsten; the Kaiser-idell collection proving to be particularly popular, and provides from its ranks the only Christian Dell lamps still in production. The "idell" in "Kaiser-idell" famously standing for "idea Dell", and he appears to have had a few of them: by his own admission in the course of his career Christian Dell developed some 500 lamp designs. Yet for us none, or none we've seen thus far, has the grace, character or charm of the Rondella.

Originally produced by Vogel & Co in Niederursel, the production of the Rondella lamps was taken over in 1928 by the newly formed Rondella GmbH, a company in which Christian Dell was a co-owner, before internal differences led to the closing of Rondella GmbH and in 1931 production responsibilities were transferred to Frankfurt based lamp manufacturer Bünte & Remmler. Obviously a very popular, or at least well represented, lamp the Rondella was not only found in the show homes of the Neue Frankfurt estates but also throughout the city administration and in factories and offices throughout the region; Christian Dell even creating an office lighting system for the AOK health insurance company offices in Frankfurt based on his Rondella.

And then, as invariably is the case with stories concerning 1920s European architecture and design, along come the Nazis...... and today the Rondella Lamp is an object which although regularly to be found in auction house catalogues, is sadly lost to the rest of us.