One of the biggest problems with Modernism is the name.

It was unquestionably modern. Which is why it became known as “Modernism”.

However, having become Modernism, it remained Modernism, and consequently “Modernism” came to imply something static.

Rather than something, well, modern.

Nowhere is this problem more visible than in discussions around Bauhaus.

Established in Weimar in 1919 Bauhaus would go on to play a central role in shaping those new ideas about art, architecture and design which swept Europe in the first half of the 20th century. And thus played a central role in the development of Modernism.

Consequently, Bauhaus is considered by many to be an historical institution. An institution which did interesting things back then from which we now have nice things to look at, but otherwise……..

Au contraire!!, cry the Vitra Design Museum, Bauhaus is as relevant as it ever was! A contention they are currently presenting in their new exhibition, The Bauhaus #itsalldesign

“A lot of contemporary design themes were also of relevance at Bauhaus”, argues Vitra Design Chief Museum Curator Mateo Kries, “social design, new technologies, who is the author of a design, the relationship between art and design, between industry and the craft trades, such fundamental questions were posed at Bauhaus and continue to dominate the design discourse today.” The Bauhaus #itsalldesign sets out to explain how Bauhaus approached these problems, while simultaneously attempting to explore not only in how far Bauhaus is still relevant, but to what extent the ideas propagated in Weimar and Dessau continue to inspire and motivate contemporary creatives.

The exhibition begins however in a very classic way with a look at the political and social context in which Bauhaus arose and a presentation of examples of those design works which helped create the Bauhaus legend. As we noted in our post on the exhibition bewundert, verspottet, gehasst – Das Bauhaus Dessau im Medienecho der 1920er Jahre, Bauhaus and its ideas weren’t universally popular in their day. Many people simply not “getting it”. Or just not liking it. Industry did however, and many were happy to cooperate with the brave young things and their brave young ideas. Not only did the Bauhaus wallpaper designs provide a nice niche market for Gebruder Rasch, but leading industrial concerns of the day such as the lighting producer Kandem or furniture manufacturer Thonet worked closely with Bauhaus designers, cooperations which regularly saw the realisation of new production concepts and methods as much as new product lines. And while it is the products and architecture which have gone on to form the basis of the popular Bauhaus legend, it is the approach to design, the approach to problems, approach to production and the underlying Bauhaus philosophy which separate Bauhaus from that which came before. According to exhibition curator Jolanthe Kugler one of the reasons behind the title of the exhibition is and was the fact that the Bauhaus philosophy, in effect, made everything design, united all arts and crafts under a unified banner. At Bauhaus #itwasalldesign

Yet ironically it is exactly this unified banner which has helped make “design” the confused, almost worthless term that it is today. Or at least the popular understanding of #itsalldesign has helped erase the line between design and styling, good and bad, useful and wasteful, necessary and pointless crap.

Everything is design. The Bauhaus legend becoming the Bauhaus cliché. Everything is Bauhaus, even when it patently isn’t, or as Jolanthe Kugler succinctly puts it “the word Bauhaus has developed into a stamp that can simply be placed on anything and then everything’s perfect.”

We all know the “Bauhaus Style Chair”, “Bauhaus Style House”, “Bauhaus Style Lamp”, “Bauhaus Style Trouser Press”, “Bauhaus Style Clock”, “Bauhaus Style Textiles”

Such objects compose the popular image of Bauhaus, the terms of reference by which Bauhaus is popularly understood. Yet invariably have nothing to do with what Bauhaus was trying to achieve. With how Bauhaus understood itself.

And the only way Bauhaus can hope to regain control over its popular image, and thus its contemporary relevance, is by showing its real self.

And this is exactly what the Vitra Design Museum attempt in the third and fourth parts of the exhibition.

And something they achieve in our opinion most successfully through the “photo” series “Space for Everyone” by Adrian Sauer in which historic photos of Bauhaus interiors have been manually “coloured in” – an approach which works very well because it presents Bauhaus in its multicoloured glory, rather than the black and white that forms the popular vision of Bauhaus. It sounds trivial, but through the addition of colour Bauhaus looks different. Normal almost. Certainly less daunting. It somehow even starts to smell different. And that is exactly what Bauhaus needs, a touch of reality amongst the legends, clichés and vapid marketing.

Students enrolled in Bauhaus, paid their fees, dropped out, had affairs, argued with tutors, cheated in exams, had brilliant ideas, had less brilliant ideas, graduated, moved away, grew up, had lives.

Hundreds upon hundreds of students and teaching staff passed through the doors in Weimar and Dessau – and would no doubt have continued to pass through the doors of Berlin had the authorities not sealed them – yet despite the years of success most people can name at best 6 Bauhäusler. Those who are a little better informed can, possibly, name up to 20. To name more than 20 you have to have been there.

The fact that #itsalldesign presents works by the likes of Ilse Bettenheim-Hoernecke, Roman Clemens or Otto Lindig next to the Wagenfelds, Breuers or Bayers of this world is not self-explanatory, is rather an active decision by the organisers based on a desire to expand the popular understanding of what Bauhaus was and what it achieved. Clearly such “new” names aren’t presented to a depth sufficient to allow any sort of opinion to be formed as to the overall quality of their individual canons, but their presence, along with a large number of lesser known and rarely seen works by the more established names, is important in completing the Bauhaus story. Or at least in attempting to, in attempting a new take on the Bauhaus story.

Something which is very important as the institution approaches its centenary.

The final section of #itsalldesign covers subjects such typography, photography or communication. The later section allowing us to pose the question that has troubled us since the exhibition was announced: Would Walter Gropius have approved of the hashtag? “Yes, definitely”, replies Jolanthe Kugler without hesitation, “because Gropius was very good at using every available method of contemporary communication in order to propagate his ideas. Similarly for us we don’t see the exhibition here as a final, enclosed, position but rather it should be seen as the start of a discussion, and where does one lead discussions today? In social media. And so for us the hashtag should underscore that we are actively looking for a discussion”

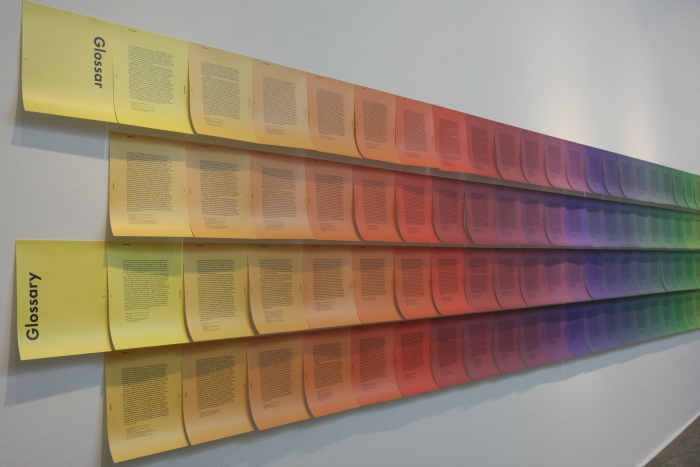

A well presented, entertaining and informative exhibition #itsalldesign provides a nice overview of and introduction to Bauhaus, including a comprehensive glossary for all who struggle with one or the other term or relationship, and through the few fresh insights and perspectives provides a much needed dose of reality to discussions concerning Bauhaus. Not least #itsalldesign reminds us that Bauhaus existed in and off its time, that real people were involved, and responded to the real challenges of the real situations they faced in their real world. It wasn’t about creating a style.

But does #itsalldesign succeed in presenting a new impression of Bauhaus that explains why Bauhaus is still contemporary and still relevant?

Very nearly.

In context of contemporary design we recently spoke to a curator who bemoaned that today you have your “star designers” and behind them, apparently, a desert. Bauhaus is popularly conceived as being no different, #itsalldesign reminds us that it was different, that the 6 Bauhäusler you can name and the eight Bauhaus objects you have seen cannot possibly stand representative for an institution that existed for over 14 years in three locations – and so by extrapolation that the situation today may also be different, if you dare to look beyond the safety of the few names you know.

Similarly #itsalldesign reminds us that Bauhaus was as much a social and economic response to the conditions of the day as it was was a creative exercise, that the objects which arose, arose for particular reasons, in a particular context and on the basis of a well considered theoretical foundation. And, and at the risk of repeating ourselves, Bauhaus wasn’t about creating a style, or as Michele de Lucchi told us in context of that other regularly misunderstood movement Memphis, “I believe Memphis is perceived more today as a style, but at that time we didn’t want to create a style but rather break down doors and free our imaginations to find new possibilities” For all the post-modern claims of Memphis their essential arguments with 1980s society were similar to those Gropius et al had with the 1920s.

All of which should cause visitors to pose themselves a few questions about contemporary society, contemporary commerce, contemporary interiors, contemporary furnishings and if, honestly, #itsalldesign?

All that works very well; what works less well is the juxtaposition of contemporary objects and Bauhaus works, or perhaps better put, what works sporadically but not completely convincingly, is the juxtaposition of contemporary objects and Bauhaus works. Woven throughout the exhibition like a golden thread intended no doubt to lead the visitor to a moment of elucidation, the concept does have its moments: the various Open Design projects on show reminding us of Bauhaus’s interest in new materials, new means of production and a braveness in accepting that such could result in new, unfamiliar form languages; similarly, the comparison of works by Hong Kong based Studio MIRO with Herbert Bayer’s graphic and exhibition design work reminds of the very important role the Bauhaus workshops played in developing modern ideas of graphic design and advertising. Other attempts work less well. That Konstantin Grcic designed a chair that looks a little bit like it could possibly have originated in Dessau in 1926 doesn’t seem relevant, or indeed particularly surprising to anyone familiar with his more commercial works, and would, in addition, tend to underscore the Bauhaus cliché rather than the contemporary relevance of Bauhaus. Similarly, the fact that Hugo Boss have created textiles with Bauhaus Style Patterns, well….. see above…..

Which isn’t to criticise the works themselves, just the decision to include them in the exhibition and for all they way they often parody much of the exhibition’s intentions and thus undermine the very good work done elsewhere.

Crowbars are an essential part of any curator’s armoury; should however always be used sparingly.

Much more convincing is the room division. At the opening of his exhibition Panorama Konstantin Grcic commented on the “challenging” space in the Gehry Building. For #itsalldesign the Vitra Design Museum have reduced the challenge by adding additional walls to create new, more manageable, spaces, and thus new display possibilities. We have no idea what Frank Gehry would say, we suspect he’d hate it, if fact we hope he would, but we find that in context of #itsalldesign the concept works perfectly and makes for a much more enjoyable exhibition than would otherwise be the case.

Bauhaus wasn’t the only school, or design/art/architecture movement of the first third of the 20th century. Is however in many respects the popular embodiment of the period.

Why? And for all why has the Bauhaus legacy survived so intact over the years? What is it that makes Bauhaus so enduringly popular?

From their contributions to the exhibition we learn that, for example, for Alberto Meda it is that Bauhaus taught us the “appreciation of how things work and not just their formal qualities”, for Antonio Citterio Bauhaus taught us about “abstraction and a holistic approach to art”; Norman Foster sees in the potential to 3D print houses a direct extension of the Bauhaus philosophy; Jay Barber and Edward Osgerby have grasped and ingested the Bauhaus philosophy of Learning by Doing; while for Mike Meiré Bauhaus taught us the value of integrating design in all aspects of a brand, from product over management and onto communication.

Which all of course perfectly explains why the Bauhaus legacy has survived so intact over the years: Bauhaus can be whatever you want it to be, whatever you want to understand it as. In terms of design and architecture Bauhaus is universal.

A fact which leaves an awful lot of room to misunderstand what the school was, what it wanted to achieve, how it pursued its aims. And for all what it can teach us today.

#itsalldesign is a good place to start questioning you’re own understanding of Bauhaus. And of contemporary design.

Or if you prefer, #itsalldesign is a good place to start questioning you’re own understanding of modern design.

#itsalldesign runs at the Vitra Design Museum, Charles-Eames-Strasse 2, 79576 Weil am Rhein, Germany until Sunday February 28th.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.design-museum.de