"Father of Eero....."

So or similar is in many circles the accepted form for referring to the Finnish architect and urban planner Eliel Saarinen.

A highly unsatisfactory term of reference and one which in many respects denies and defames how much more there is and was to the man and his talents.

Gottlieb Eliel Saarinen was born on August 20th 1873 in the remote eastern Finnish town of Rantasalmi where his father served as a Lutheran pastor. In 1875 Eliel's father was posted to a Finnish speaking community near Saint Petersburg where the young Saarinen remained until being sent to boarding school in Vyborg aged ten. In 1890 Eliel Saarinen moved to the Finnish Real Lyceum in Tampere before in 1893 he enrolled simultaneously in the Architecture Department of the Helsinki Polytechnic Institute and the Art Department of Helsinki University where he studied painting, according to Saarinen "the former was the choice of a cool mind, the latter the demand of a warm heart."

In 1896, and while still a student, Eliel Saarinen established an architectural practice with fellow students Herman Gesellius and Armas Lindgren. Inspired by the likes of Louis H. Sullivan, Henry van de Velde and Otto Wagner the trio began questioning contemporary architectural conventions and armed with the invincibility of youth formulated their response to the challenges of the period. Remembering back to the turn of the century Saarinen would later remark, "architecture was a dead art form. It had gradually become the business of crowding obsolete and meaningless stylistic decoration on the building surface. And it was sacrilege to break with such a procedure, which was held to be as sacred as the dogmas of religion." Yet break them the trio did.....

In March 1897 Gesellius, Lindgren & Saarinen won their first competition, a four storey house for Helsinki based businessman Julius Tallberg in the Katajanokka suburb of the Finnish capital. A relatively ornamentation free construction with Art Nouveau leanings, and according to Marika Hausen a house which contrasted greatly with the dominating Neo-Renaissance architecture of that period in Finland, the Tallberg building, in conjunction with subsequent well received competition entries, quickly established the practice a reputation for modern designs and individual, free-thinking approaches, before in 1898 Gesellius, Lindgren & Saarinen made their first major breakthrough winning first prize in the competition for the Finnish pavilion for the 1900 World's Fair in Paris. A single storey, quaintly Gothic, wooden construction styled to look like masonry, the dominant feature of the pavilion is, was and always will be an outrageously decadent tower that wouldn't look out of place in one of Ludwig II's more improbable fantasies. Not unattractive you understand. Just plain weird.

Fired by the success of Paris and their increasing position as one of the leading contemporary Finnish architectural practices, subsequent years saw Gesellius, Lindgren & Saarinen complete a series of prestigious commissions both at home and abroad, including private houses in the German towns of Alt Ruppin and Bad Honnef, the National Museum in Helsinki and the city's new central railway station, a project which was to become one of the practice's most defining works, and one of their last. In 1907, during the construction of Helsinki central station, Eliel Saarinen split from Gesellius and Lindgren to establish his own office.

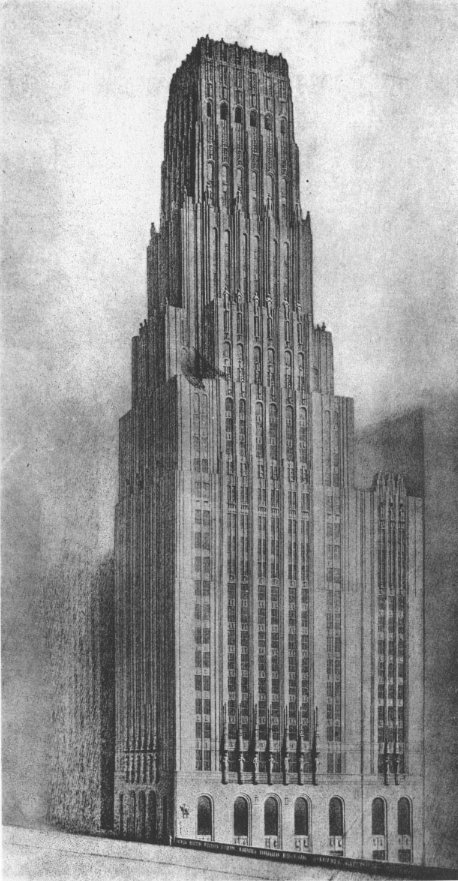

Having gone solo Eliel Saarinen completed numerous prestigious architectural projects, both in Finland and overseas, in addition to increasingly busing himself with questions of urban planning, including working on projects for cities as varied as Budapest, Canberra, Tallinn and Helsinki, before in November 1922 he submitted his entry for the Chicago Tribune Tower competition: a competition entry which was to become one of those wonderfully serendipitous moments of fate.

Awarded second place Saarinen's entry demonstrated his move to, almost, total rejection of ornamentation and an increasing concentration on formal clarity in a monumental work which harked back to historical archetypes without referencing them directly. Whether by good design or good fortune Saarinen's paired down Gothic concept, essentially denuded of ornamentation but retaining enough detailing so as not to offend 1920s American sensibilities, met with enthusiastic critical acclaim and was praised by the jury as showing "a remarkable understanding of the requirements of an American office building"; and as a composition was certainly more accessible for American eyes than entries by other Europeans, perhaps most notably, Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, Max Taut or Vienna based Werkstatt für Massenform, whose entries were less the stuff the American Dream is made of as the American Nightmare, and works which if realised would arguably have put the modernist cause in America back ten years rather than advancing it as Saarinen's entry unquestionably did, indicating as it does the unstoppable move to Art Deco.

Buoyed by the success of the entry and motivated by the positive response, Eliel Saarinen emigrated to America in 1923 together with his wife Loja and their children, Eva-Lisa and Eero.

Exactly why the Saarinen's moved to America is unclear, even Albert Christ-Janer can't come up with a decisive reason, and that despite having spent untold hours interviewing Saarinen for his otherwise fulsome biography. What is clear however is that following the positive reception of his competition entry the Chicago Tribune invited Eliel Saarinen to America. Once there, and having been exposed to the reality of contemporary American architecture and the American way of life Saarinen, presumably, realised that there were at that moment more opportunities for him in the American economic boom than in Europe, and certainly in Finland, and so decided to cross the Atlantic and try his luck. And regardless of the reasons, it was to turn out to be correct decision: America proving to be a very happy hunting ground for Eliel Saarinen, and Eliel Saarinen becoming an important protagonist in the development of 20th century American architecture and design.

Shortly after settling in America Eliel Saarinen took up a teaching position at the University of Michigan, in the course of which he tutored a certain J. Robert F. Swanson. Following his graduation Swanson established a practice with Henry S. Booth. Booth's father, the newspaper publisher George Gough Booth, offered the pair a job building a new school he was planning to establish on his Cranbrook estate in Bloomfield Hills near Detroit, and Swanson and Booth Jr. approached Eliel Saarinen to ask if he would be interested in joining the venture. With a little persuasion, and having discussed the wider aims of the school with George Gough Booth, Eliel Saarinen agreed and in 1925 became the project's chief architect. The Cranbrook School for Boys was completed in 1928 and the neighbouring Kingswood Girls School in 1931, in 1932 Eliel Saarinen was appointed President of the newly established Cranbrook Academy of Art before completing the Cranbrook Art Museum and Academy Library buildings in 1942.

Essentially conceived by Booth as a location where America's brightest architecture, art and design talents could study in peace and depth in America rather than having to travel to Europe, the Cranbrook Academy of Art was to nurture some of the most important talents of post-war American creativity, including, amongst others, Harry Bertoia, Eero Saarinen, Charles Eames, Ray Kaiser and Florence Schust, the future Florence Knoll.

In addition to his work at Cranbrook Eliel Saarinen's years in America were defined by constructions such as the Kleinhans Music Hall in Buffalo, the Des Moines Art Center, Iowa and Christ Church Lutheran, Minneapolis, works he often completed in partnership with Eero Saarinen.

In 1946 Eliel Saarinen retired from his position at Cranbrook, remaining however head of the Department of Architecture and Urban Design. Eliel Saarinen died at his home in Cranbrook on July 1st 1950.

It is often said that Eliel Saarinen lived his life in two halves. The first half a Finish architect in Finland, the second an international architect in America.

While obviously an outrageous oversimplification, there is just enough of a germ of truth in the statement to make it valid. And to allow us to exploit it.

With his consequent move away from historicism and his development of a Finnish vernacular approach to modernism devoid of unnecessary kitsch or romanticism Eliel Saarinen not only helped develop a new understanding of architecture in Europe, but a new understanding of Finland, both in Finland and overseas. The late 19th/early 20th century were politically and culturally troubled times in Finland and Eliel Saarinen help the Finns develop a sense of national identity, albeit without the sense of national pride that often muddies such waters. Or as Alvar Aalto writes "Eliel Saarinen was helpful in eliminating some of the architectural illiteracy and some of the inferiority complexes in a country which, because of its isolation and the difficulty that outsiders encounter in learning its language, has been and still is removed from the larger cultural centres of the western world." Words poetically echoed by the jury of the Tribune Towers competition and their all too obvious pleasure that, "only one foreign design stands out as possessing surpassing merit, and this truly wonderful design did not come from France, Italy or England, the recognized centres of European culture, but from the little northern nation of Finland"

There is just something wonderfully demeaning yet spiritually uplifting in the term "little northern nation".

And just has he helped Finland find a sense of identity so to did Eliel Saarinen through his work at Cranbrook help post-war American designers find a voice and form language appropriate for their times.

Although it is arguable in how far Eliel Saarinen was personally responsible for the success and subsequent renown of Cranbrook, in his 25 years association with the school he built it both physically as an architect and pedagogically as President and department head. In addition it was Saarinen who was impressed enough by the work of Charles Eames to personally offer him a fellowship at Cranbrook and who then invited the young Eames to work on numerous projects, including the development of furniture designs and who thus was an important influence on Eames as he established his own design philosophies.

It's unfair to compare Cranbrook with Bauhaus and certainly Saarinen with Gropius, but in their own way both helped guide a new generation of designers and architects towards a new future, and thus given the central role Eliel Saarinen played in nurturing modern architecture and design in America a more fitting and appropriate way to introduce Eliel Saarinen would surely be "Father of American Mid-century Modernism..... "

Happy Birthday Eliel Saarinen!

PS: And for all who think we may have forgotten, we haven't: Happy Birthday Eero Saarinen!