Much as we all like to assume we all know everything there is to know about modernism, and convinced as we all are that we can name all the important protagonists and their key works.

We largely can't.

We can largely scratch the surface of modernism and name a handful of the best known protagonists and name a few of their better known works.

Just how little the vast majority of us truly understand about modernism is currently being laid bare in the exhibition "Der entfesselte Blick – Die Brüder Rasch und ihre Impulse für die moderne Architektur" - The Unfettered Gaze. The Rasch Brothers and their Influences on Modern Architecture - at the Marta Herford museum in Herford, Germany.

The Rasch brothers?

Exactly.

Heinz Rasch was born in Berlin on February 15th 1902 and began studying architecture in Hannover in 1920 before switching to the Technische Hochschule Stuttgart in 1922 from where he graduated in 1924. His brother Bodo was born a year later on February 17th 1903, began studying agriculture in 1922, graduating from the Landwirtschaftliche Hochschule Hohenheim in 1926. In a situation very reminiscent of Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec, the Brothers Rasch first cooperated in 1923 when younger brother Bodo assisted older brother Heinz in his so-called "Werkkunst Arche" venture, essentially a small workshop where they developed simple wooden furniture and lighting projects. In 1926 however things became more professional with the establishment of the company "Brüder Rasch. Hochbau, Möbelbau, Werbebau" in Stuttgart; an atelier which according to the exhibition curators quickly developed into an important meeting point of the burgeoning Stuttgart architecture, artistic and creative community of that period. In 1927 Heinz and Bodo Rasch were commissioned by Mies van der Rohe and Peter Behrens to furnish two houses for the Weissenhofsiedlung exhibition and over the coming three years developed numerous architecture, urban planning and design projects; projects which although not actually realised not only brought the brothers into close contact with many of the leading protagonists of the era but also helped them establish a reputation for the advanced nature of their thinking and planning. In addition to their architecture and design work Heinz and Bodo Rasch also worked as authors and editors, most notably publishing the works "Wie Bauen?" in 1927 and "Der Stuhl" in 1928, the accompanying text to the Stuttgart exhibition of the same name. In 1930 Heinz Rasch moved to Berlin and at the same period the brothers Rasch suffered an unbrotherly falling out which put paid to further joint projects; thus the fruitful period of co-operation lasted just four short years. Post war both brothers continued their architecture and design work independently of one another: albeit largely without the plaudits and public attention of the 1920s. Bodo Rasch died on December 27th 1995, Heinz Rasch on 27 November 1996.

Although positioned as an architecture exhibition Der entfesselte Blick opens with an exploration of Heinz and Bodo Rasch's publishing, interior design and furniture design work. A central place in which is given over to their role in the development of the cantilever chair.

Largely the result of elementary research on the ergonomics of sitting and of the optimal construction of load bearing structures which the brothers had conducted since 1923, the cantilever chairs developed by Heinz and Bodo Rasch were first produced in 1924, so some three years before Mart Stam unveiled his Kragstuhl: yet never achieved a market to match those of their contemporaries. Far less a fame. One could add that much like Heinz and Bodo Rasch their chairs have become anonymous. Characteristic of the Rasch brothers cantilever chairs is a diagonal frame, a design concept and construction principle which according to Axel Bruchhäuser, Chief Executive of the German furniture manufacturer TECTA, founder of the cantilever chair specialised Kragstuhlmuseum, and personal friend and associate of Heinz Rasch, could, explain why they never established themselves. "Heinz Rasch believed that on account of the geometric divisibility of a standard room only cubic chairs such as those from Mart Stam could establish themselves; because they repeat this cubic form. That is chairs with quiescent vertical and horizontal lines have a chance whereas those which contradict this spatial harmony do not." And certainly when you look at the history of furniture design in general it is difficult to argue with Heinz Rasch's logic.

As if to compound the lack of success with and recognition for their cantilever chair designs, there is a certain irony in the fact that it was Heinz Rasch who both helped Mart Stam solve the construction and durability problems of his design and who also introduced Mart Stam to the furniture producer L + C Arnold, who had been producing Heinz Rasch's diagonal cantilevers since 1924 and who subsequently produced Stam's cantilever chair for the Weissenhofsiedlung exhibition. In effect Heinz Rasch set Mart Stam on his path to posterity, and so blocked his and his brother's paths.

Having used the brother's place in the history of furniture design to help introduce the dominating architecture and design philosophy's of the late 1920s, Der entfesselte Blick moves on to its principle focus, the brother's architectural output.

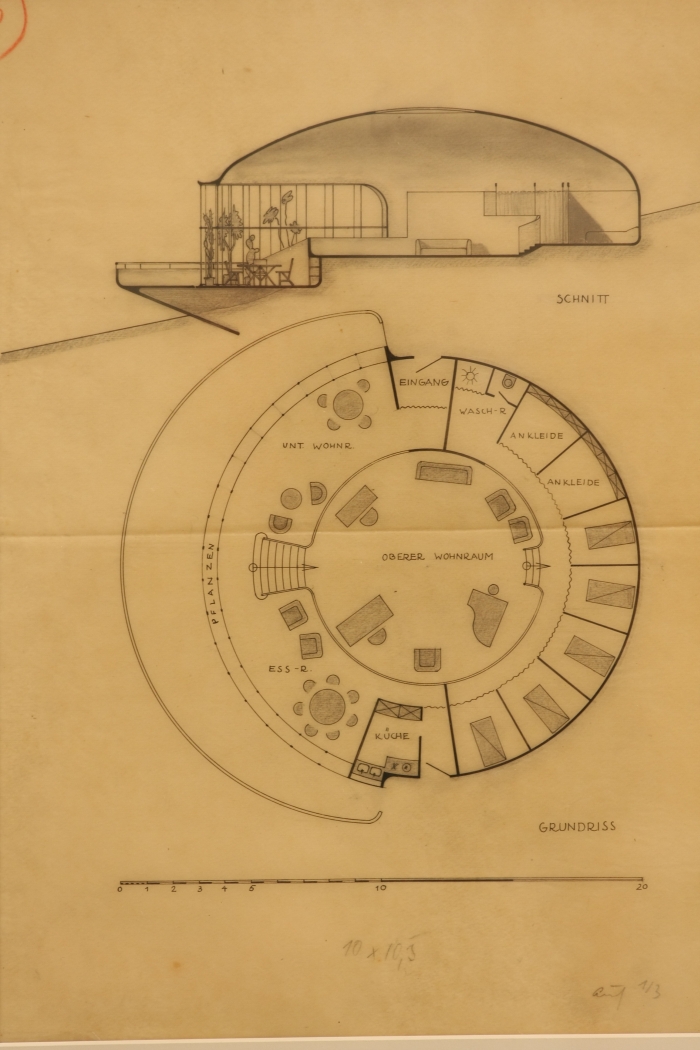

To this end the exhibition concentrates on three areas of architecture in which the brothers were especially active: Pneumatic Structures, Container Architecture and perhaps most importantly, Suspension Houses. Beginning by explaining the work undertaken by Heinz and Bodo Rasch the exhibition presents sketches, models and photographs which succinctly explain the focus of the brothers' architectural and urban planning work, the goals they set themselves, the visions and principles that stood behind the work and how they attempted to realise their visions, while all the time placing their research and project planning in context of the period it was developed.

Having introduced the three central themes the exhibition then moves on to explain how other architects subsequently realised many of these ideas, if you will explains the brothers and their oeuvre through constructions realised by architects in later eras yet often using principles, techniques and ideas reminiscent of those developed, or at least anticipated, by Heinz and Bodo Rasch: "Pneumatic Structures", for example, being illustrated by projects including Coop Himmelb(l)au's' Wolke 68 and Foster and Partners' Air Supported Office; "Suspension Houses" are represented by amongst other constructions the Olivetti Towers in Frankfurt by Egon Eiermann; while "Container Architecture" is illustrated by, for example, Richard Rogers Partnership's Inmos microprocessor factory and Nicolas Grimshaw's new grandstand for Lord's Cricket Ground in London.

In doing so Der entfesselte Blick very neatly and competently demonstrates that, in principle, one can find traces of the Rasch brothers thinking in all decades since the war.

But can one talk of an influence? There the exhibition is more vague. The impression one gets is that one should be able to, that the curators want you to believe that there is, yet there is no direct evidence presented. Only evidence that the Rasch's were often amongst the first to work on certain concepts, to work on achieving certain architectural solutions. But if any of the later architects were aware of Heinz and Bodo Rasch? If they had seen any of their sketches?

Similarly, while the brothers role in the development of 1920s furniture design is clearly explained, the question of in how far Heinz and Bodo Rasch directly influenced the development of architecture in the 1920s remains open.

Being as they were in close contact with the likes of Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, Mies van der Rohe et al it is inconceivable that a regular and frank exchange of ideas and opinions didn't occur. But in how far the ideas and positions Heinz and Bodo Rasch held and expressed in these exchanges actually influenced their contemporaries, remains unanswered. And ultimately is a question for those researching the works of Gropius, Mies, Breuer et al to research and answer. In effect to look more closely in their archives and attempt to follow any potential threads backwards.

What the exhibition does however do very well is what the Marta Herford's artistic director Roland Nachtigäller hoped it would, namely present new aspects, new perspectives and cast new light on the modernist era. It is all to easy to forget that a period such as modernism was more than handful of architects and designers busily creating everything. There were also the likes of Heinz and Bodo Rasch. And once you understand that, once you marvel at the work they were producing and realise the foresight and vision which it contains, you not only understand modernism as a wider more multi-faceted and alinear epoch than before but you also start to question more about our own age. Important is not just those buildings or those furnishings that are produced, built, sold and rendered, but also the research and the development work being undertaken by untold Heinz and Bodo Raschs. Work that may not be realised for a generation or two to come and whose authors may never get the full credit they deserve.

Consequently just as Alvar Aalto - Second Nature at the Vitra Design Museum is an exhibition for all who want to understand Aalto beyond organic flowing structures and birch, or just as Schrill Bizarr Brachial. Das Neue Deutsche Design der 80er Jahre at the Bröhan Museum Berlin is for all who want to to understand 20th century German design beyond Bauhaus, Dieter Rams and Egon Eiermann, so is Der entfesselte Blick an exhibition for all who want to understand architecture beyond the normal blithely accepted "contemporary" nature of all "new" ideas, to understand that architectural concepts not only take time to reach full maturity, but often need to pass through several practitioners to achieve their final form. And of course for all who want to understand modernism beyond their current, limited, knowledge.

What Der entfesselte Blick explicitly doesn't do is explain how and why Heinz and Bodo Rasch could become so anonymous. Largely because no one seems to have a definitive answer, the reason being most likely a chain of barely related yet additively damaging facts: the personal conflict between the brothers, the economic crisis of the Weimar Republic, the Second World War, the lack of commercial success with their furniture projects, the fact that many of their architectural projects could only be realised once technology was up to the task, and that those architects and designers who were first to make use of the new technology went down in history as the authors of the idea. Plus one shouldn't forget that, generally speaking, all the pre-war modernist architects who went on to find post war fame and fortune found it in America: Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Breuer. Those who didn't cross the Atlantic didn't cross into the public domain, or at least not so immediately or sustainably: Mart Stam, Victor Bourgeois, Hans Scharoun, Heinz and Bodo Rasch.

However slowly but surely the world is learning more about the true depth and variety of those practitioners who helped make modernism the important era that it was. It is to be hoped that Der entfesselte Blick helps Heinz and Bodo Rasch establish the status they unquestionably deserve. Or perhaps better put, re-establish the status they once held.

But was there resentment from the brothers at their lack of recognition and subsequent fall into anonymity? Did it not grate? To answer this question we'll give the last word to Heinz Rasch. In his last letter to Axel Bruchhäuser he reflected on the place his work has taken in the history of furniture design, and did so in the most delightfully humble, touching, eloquent and genuinely unassuming manner. He was referring as we say to his furniture design work, but we'll take the liberty of expanding it to the question of his whole oeuvre.

".....with my own models I had no luck, but I was never jealous and lived essentially for the success of others. I considered that the natural duty of any architect who sees in himself only a craftsman."

Der entfesselte Blick – Die Brüder Rasch und ihre Impulse für die moderne Architektur runs at the Marta Herford, Goebenstraße 2–10, 32052 Herford, Germany until Sunday February 1st.

Full details can be found at http://marta-herford.de