Born on April 2nd 1914 Hans Jørgensen Wegner is without question one of the most important designers of the so-called Danish Modern movement.

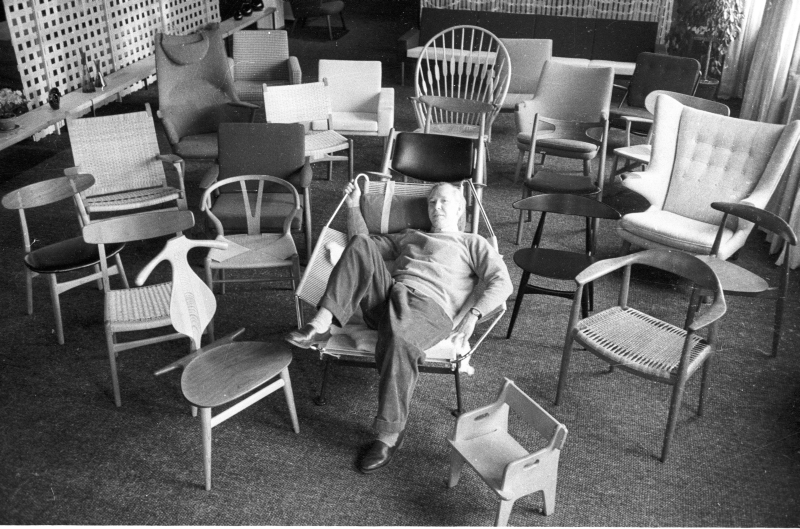

Works such as the Peacock Chair from 1947, the 1949 JH501, an object often referred to simply as "The Chair" or his 1949 CH24 Wishbone Chair, his best selling creation, largely helping define Danish design in the 1940s and 1950s. Golden decades that still dominate the public persona of the Danish design tradition.

Hans Jørgensen Wegner is equally unequivocally one of the most academically neglected designers, and is, for example, the subject of considerably fewer books than his contemporaries.

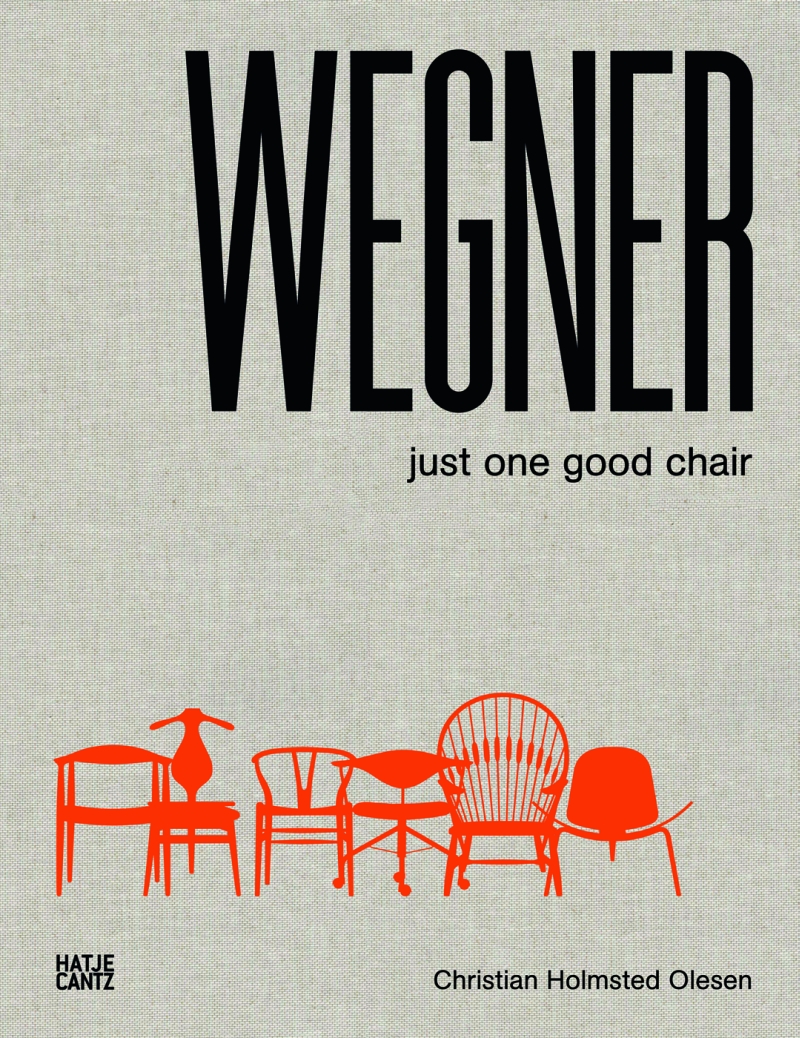

And so it is especially welcome that to mark Wegner's 100th birthday not only is the Designmuseum Danmark in Copenhagen staging one of the most comprehensive Wegner exhibitions ever conceived, but are also publishing an accompanying book on the designer and his work: WEGNER – Just one good chair.

Written by Christian Holmsted Olesen, the Designmuseum Danmark's head of exhibitions and collections, and largely based on video interviews recorded with Wegner before his death and interviews with those who knew, understood and worked with Wegner, Just one good chair not only documents Hans J. Wegner's journey from teenage carpentry apprentice to the Grand Doyen of 20th century Danish furniture design, but also contains a register of Wegner's works.

The first thing to say is that Just one good chair is a little too sickly sweet for our tastes. Olesen is clearly a fan of Wegner, and who isn't, but the book is written in such uncritically positive tones, occasionally unbearably so, that it distracts from the subject at hand and, at times, almost turns the reader away from the designer. Wegner's work doesn't need the hagiography. Just explaining.

However, read through the sickly sweet prose and Just one good chair provides a comprehensive and very informative overview of Hans J. Wegner's approach to his work and his understanding of his responsibilities.

For all his responsibility to the traditions of Danish carpentry.

Born in the southern Danish town of Tønder as the second son to shoemaker Peter Mathiesen Wegner and his wife Nicoline, Hans J. Wegner spent a considerable part of his early years hanging around his father's workshop, whittling on odds and ends of wood, before leaving school at 14 to begin an apprenticeship with local carpenter H. F. Stahlberg. According to Olesen an important moment in the young Wegner's career came in 1935 when, while completing his military service in Copenhagen, he visited the annual exhibition of the Copenhagen Carpenters' Guild, and realised that if he was going to achieve his aim of becoming a Master Carpenter, he was going to have to seriously improve his skills. As a consequence, in 1936 Wegner enrolled in the carpentry class of the Kunsthåndværkerskolen, the Copenhagen Arts and Crafts School: an institution which he then left two years later to take up a position with Arne Jacobsen and Erik Møller. In 1942 Hans J. Wegner established himself as freelance designer and architect. The rest, as they say.....

Although Wegner only attended the Arts and Crafts School for two years, as Christian Holmsted Olesen explains, in the course of these two years the foundations were laid on which Hans J. Wegner was to establish his career.

Firstly the teaching at the Arts and Crafts School was almost completely based on the design principles of the institutes guiding father Kaare Klint, an architect and designer with an almost fanatical addiction to traditional forms and traditional crafts. Although in his adoption of, for example, organic forms and suspended seats Wegner distanced himself from aspects of Klint's thinking, in other respects, most notably his dogmatic adherence to handicrafts and his reference to established historical forms, Wegner clearly remained a designer influenced by Klint. An important aspect of the Arts and Crafts School's concept was the measuring and drawing of historical furniture models. That the school was housed in the Designmuseum Danmark there were no shortage of examples to choose from, and during his time at the school Wegner was introduced to numerous chair forms which he regularly referenced in his own designs.

Although Kaare Klint was the guiding force behind the Kunsthåndværkerskolen, during Wegner's time the school was under the directorship of Klint's former pupil Orla Mølgaard-Nielsen, a man who not only to set up the position for Wegner with Jacobsen and Møller but who also introduced Wegner to the carpenter Johannes Hansen, with whom Wegner subsequently cooperated for 26 years and in whose workshops many of Wegner's most important projects were realised. And perhaps most importantly it was Orla Mølgaard-Nielsen who in 1946 arranged a job for Wegner in Copenhagen, thus allowing him to return to the capital from his war time base in Aarhus. And so to resume his cooperation with Johannes Hansen, and so realise those projects that were to establish his reputation.

At the Kunsthåndværkerskolen Wegner also met Børge Mogensen, an man with whom he was to enjoy a lifelong friendship and professional relationship - even if, as Christian Holmsted Olesen makes clear, the two often had strongly opposing views on design questions. Although one must also add that in many respects these differences and the pair's regular, or better put, constant, discussions, pushed both designer's thinking forward and so helped them form their own, individual, approaches to design.

In addition to documenting the importance of the Arts and Crafts School to Wegner's development Christian Holmsted Olesen also highlights and underscores the important role played in Wegner's career by the Copenhagen furniture dealer Eivind Kold Christensen, the man who brokered Wegner's contact to important commercial furniture producers of the period including Getama, A. P. Stolen and Carl Hansen & Søn, discusses Wegner's, often too easily forgotten, development of low-cost furniture systems, explores the importance of Wegner's three month tour of America in 1953 and also provides ample evidence that Hans J. Wegner clearly had something of a stubborn streak.

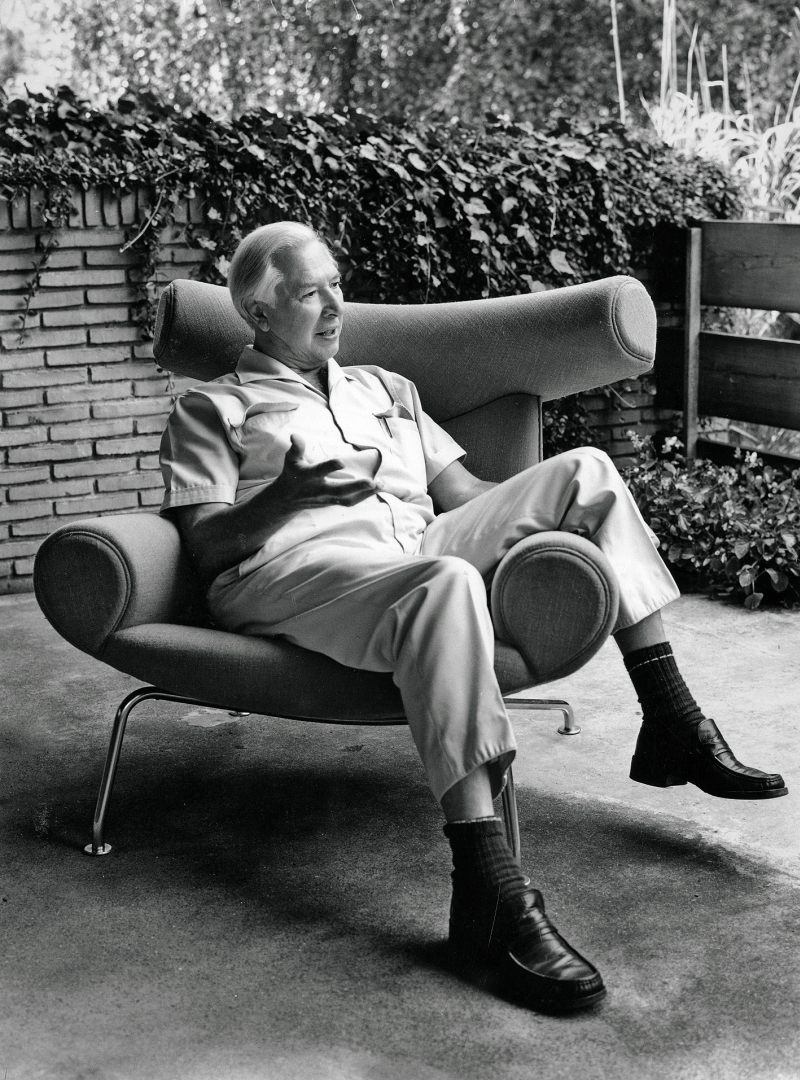

A stubborn streak which may of course also explain why the Ox Chair was his personal favourite amongst his chairs.

During his 1953 American tour, Olesen recounts, Wegner was approached with a proposal to have his work serially produced in America, and thus made available, at an affordable price, to a mass public au fait with organic design through the works of Eames, Saarinen et al. Wegner said no! For Wegner his furniture had been created to be made by craftsmen, by hand, in Denmark. Anything else was inconceivable. In the 1970s, however, the changed economic and market conditions in Europe meant that Wegner had to accept the partial machine production of his furniture. Albeit still exclusively in Denmark. These changing conditions also meant that Wegner's preferred dark, tropical woods were no longer en vogue. Ejnar Pedersen, CEO of manufacturer PP Møbler, remembers that when they took over production of the Valet Chair from Johannes Hansen in 1991 he asked Wegner from which wood it should be made, ""pine and teak" replied Wegner, "we'll never sell those" I said, "it must be maple." "You and your maple", answered Wegner, "do what you want!". And so we made 50 in maple, 50 in mahogany and 50 in pine and teak. When the 50 in maple had been sold we had only sold 20 in mahogany and 20 in pine and teak"

Which all of course reminds us of Arne Jacobsen's, initial, stubborn, refusal to make his three legged Ant Chair four legged as Fritz Hansen wanted. The subsequently developed four legged Series 7 chair of course going on to become Jacobsen's most commercially successful chair.

Events which nicely highlight the perils of leaving certain decisions to designers alone.

In addition to Christian Holmsted Olesen's text WEGNER – Just one good chair is richly illustrated, featuring some 240 photos including images of Wegner at work, impressions of his sketches and other art works in addition to numerous photos of Wegner's furniture designs.

From the very beginning Olesen makes clear that part of the aim of Just one good chair is to de-construct the myth of Hans J. Wegner as simply a genial carpenter and instead present Wegner as an experimental designer, an artist and as a master of materials and construction with an especially strong affinity to form.

For us he succeeds. Partly.

Having read Just one good chair we don't see Wegner as having been genuinely experimental in the classical sense. Olesen does however convincingly present a profile of a man who understood the traditions of Danish carpentry, understood the value of proven, established forms and who was one of the first practitioners to understand the importance of not only interpreting these proven, established forms in new, modern ways, but of also of re-interpreting the basic tenets of Danish carpentry. And who thus helped advance a new approach to furniture design and an aesthetic that perfectly complimented the uncompromising formality of the dominant modernist architecture of the period.

Wegner didn't break the mould, he planed it down, layer for layer, and re-formed it with "almost provocative" curves.

The title of the book is a reference to a 1952 quote from Wegner, "If only you could design just one good chair in your life . . . But you simply cannot"

Wegner knew such was impossible, not because he couldn't design chairs, but because, much like Egon Eiermann, he always felt one could do better, one could perfect what one had created, or as Olesen quotes him, "there is nothing that you can't improve." Just one good chair eloquently explains how Hans J. Wegner pursued this perfection.

As we say, informative and enlightening as Christian Holmsted Olesen's text unquestionably is, it is, for us, a little too sweet; however, if you consider it as a literal butterscotch drizzled marzipan meringue torte, then it makes the perfect birthday cake.

Happy Birthday Hans J. Wegner!

WEGNER – Just one good chair by Christian Holmsted Olesen is published by Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern and is available in English and German.

The Danish version, WEGNER - bare een god stol, is published by Strandberg Publishing, København.