Architecture | Artek | Design Calendar | Designer | Producer | Product

Alvar Aalto, "The Humanizing of Architecture - Functionalism must take the human point of view to achieve its full effectiveness" Technology Review, Volume 43, Number 1, November 1940, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

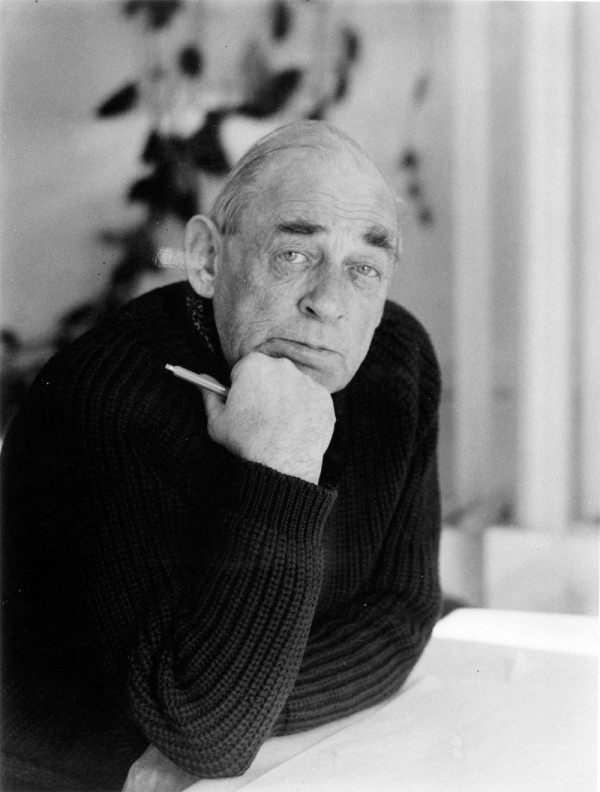

Born on February 3rd 1898 in Kuortane, Finland, Hugo Alvar Henrik Aalto grew up in the southern Finnish town of Jyväskylä before moving to Helsinki in 1916 to study architecture at the Technical University. Following his graduation in 1921 the young Alvar Aalto spent two years "on the road", including periods in Helsinki, Stockholm, Gothenburg and Tallinn, before returning to Jyväskylä in 1923 where he opened his first practice, completed his first notable projects and married his first wife, and first business partner, the architect Aino Marsio. In 1927 the Aalto's moved to Turku before moving on again in 1933 to Helsinki. From the Helsinki office Alvar Aalto completed over 400 architectural, exhibition design and interior design projects throughout Finland, Europe and further afield, in addition to holding a Professorship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Alvar Aalto died in Helsinki on May 11th 1976.

Although primarily an architect Alvar Aalto is probably most immediately remembered today for his furniture, and for all for the contribution his furniture has made to the development of 20th century furniture design.

Not that his first furniture designs indicated what was to come. Principally created in context of interior design projects Alvar Aalto's early furniture largely played safe, retaining the familiar form language of the day: rustic Americana, traditional hand-crafted English, neoclassical Swedish, et al.

As with Alvar Aalto's architecture it took his conversion to functionalism to bring about changes in his furniture design. We weren't there, we can't confirm exactly what happened, but by all accounts the change took place suddenly, "as if by magic" in 1927, and while there were unquestionably several reasons for Aalto's conversion, the Weißenhofsiedlung Stuttgart appears to have played a very important role. Aalto himself didn't visit Stuttgart, but several of his colleagues did and by all accounts their reports strongly influenced Alvar Aalto.

Regardless of why, his conversion was certainly timeous. In 1929 Aalto won the competition for a new tuberculosis sanatorium complex in Paimio, Finland with a construction that not only expressed the ideals and principles of functionalism more elegantly, more explicitly, than any other Scandinavian building of the period, but which also reflected Aalto's philosophy of functionalism in terms of functional to the user rather than the functional to machines/economics that stood behind much functionalist architecture. As a project Paimio both established Aalto's reputation as an architect and gave the world the first relevant, truly revolutionary, furniture pieces from Alvar Aalto.

Following his conversion to functionalism Alvar Aalto began experimenting with the furniture ideas developed by the leading modernist designers, for all the Bauhäusler. Was however unconvinced by the all pervasive steel tubing used in the majority of the known objects.

Which of course brings us back to the entry quote and the need to rationalise "the selection of materials which are most suitable for human use"

For Alvar Aalto the answer was to be found in the birch forest of Finland, and consequently he set himself the aim of creating "modern chairs with the same qualities as those of steel tube furniture, but built solely of wood, a material with more pleasant tactile qualities."

For the Paimio sanatorium project Aalto's motivation for creating wooden furniture was more immediate: "the first versions were created in metal; however we quickly switched to wood as the nickel and chrome plated steel furniture struck us as too hard psychologically for a milieu with the sick. And so we started working in wood, using this warmer and more pliant material to create furniture more fitting for the ill."

From a plethora of objects created for the Paimio sanatorium the most important, and famous, piece is the so called Paimio Chair, an object marketed today by Artek as Armchair 41. Visually reminiscent of Marcel Breuer's Wassily chair, Jean Prouvé's Cite armchair or indeed Josef Hoffmann's 1908 Sitzmaschine, the Paimio Chair is essentially a cubic moulded birch frame in which is hung an elegantly sweeping moulded plywood seat shell. Quite aside from being a genuine technical masterpiece that expanded the borders of what was possible with moulded wood and so opened up a new world of possibilities; with its reduced, open form the Paimio Chair can also be considered as the very epitome of the new aesthetic propagated by the modernist movement. And from a pure product design perspective one must also note that the angle of the back rest was, allegedly, set so as to offer optimal comfort to those recovering from tuberculosis. Allegedly in the sense that we can find no direct confirmation from Aalto himself, just from secondary sources.

Inspired by the technical success of the Paimio Chair Alvar Aalto went on to develop a moulded plywood cantilever chair, marketed today by Artek as Armchair 42, before realising his most refined and complete work, the three legged Stool 60. Or perhaps better put, the L-leg which was subsequently developed into the three legged Stool 60. A story and history we discussed in context of a 2013 exhibition at Ungers Archiv für Architekturwissenschaften Köln, and a text to which we refer you dear reader.

Post World War II Alvar Aalto - as with so many furniture architects of the era - stopped designing furniture for his architectural projects and so, in effect, stopped designing furniture. The few pieces that he did produce post war lacking the pioneer spirit of his 1930s work. However, despite the fact Alvar Aalto's experimentation and invention in the field of moulding wood only lasted half-a-dozen years it was to go on to motivate both his contemporaries and subsequent generations of designers: the best examples probably being Charles and Ray Eames, Egon Eiermann, Eero Saarinen, Arne Jacobsen.... We could go on.

And indeed today a visit to almost any student showcase exhibition will provide evidence of Alvar Aalto's importance and enduring legacy.

A legacy that, for us, has its origins in the sentiments of former Architectural Review editor J.M. Richards who recalling his own reaction to seeing Aalto's furniture at a 1933 exhibition in London wrote: "The furniture had a freshness and unexpectedness which was derived from his adventurous exploration of new techniques. It had wit, which it owed to an unusually direct connection between ends and means. It was original, not as a result of trying to be so, but because of the serious thought that had been given to basic principles. Aalto's personality, too, showed freshness, wit and originality, and the reasons were the same."

Happy Birthday Alvar Aalto!