Following quickly on the heels of the Eileen Gray retrospective at the Centre Pompidou Paris, on Friday February 22nd the Musée d'Art Moderne de Saint Etienne Métropole is opening an exhibition devoted to another Grand Dame of French Modernism, Charlotte Perriand.

However, in contrast to the all-encompassing Eileen Gray exhibition, "Charlotte Perriand et le Japon" focuses on one period of Charlotte Perriand's biography. Or better put the role played by one country in her biography.

Born in Paris in 1903 Charlotte Perriand's childhood was divided between the family in home in Paris and her grandparents' domicile in the rural Savoie. In 1920 she enrolled in the Ecole de l’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, graduating in 1925. Trained in the Beaux-Arts tradition of the day, Perriand's early works were very much of a decorative, Art Noveau style, then in 1927 she became acquainted with the writings of a certain Le Corbusier and his diatribes against the decorative and for the functional.

Seduced by the conviction of his arguments and imbibed with the self-confidence of the age, she knocked on Le Corbusier's atelier door to ask for work.

"On ne brode pas des coussins ici." came the terse reply. Loosely translated, "We do not embroider cushions here."

Eventually however Le Corbusier conceded to let Charlotte Perriand join his small team - potentially, as Mary McLeod argues, because he needed somebody who could help him design furniture, and he saw that person in Charlotte Perriand. Or as Charlotte herself theorises, with her "new woman" look she radiated a forceful charm that couldn't be ignored. Regardless of the reason, their partnership - generally as a triumvirate with Le Corbusier's cousin Pierre Jeanneret - was to become one of the most successful and important of all modernist era studios outwith the hallowed Walls of Bauhaus.

In 1937 Perriand left Le Corbusier to pursue other projects, before in 1940 she was approached to work in Tokyo as an industrial design advisor to the Japanese Ministry of Trade and Industry.

While admittedly in context of our 21st century understanding of the world, the Japanese asking a European to advise them on industrial design may appear similar to an Inuit asking a European for advice on "What to do with all this snow?"; in the context of the age it made perfect sense. Following the demise in 1868 of the Tokugawa shogunate and so two centuries of feudal military rule, civilian Japan had been slowly finding its place in the modern world; yet one area where it consistently struggled to achieve success was international trade. Again, somewhat ironically.

A largely peasant, agrarian nation, Japan was proficient in handicrafts and artisan production, but not at producing goods that were of a quality suitable for export. And so in the late 1920s the decision was made to recruit foreign experts to advise key industries.

Against this background, in early 1940, and mediated by the Japanese architect Junzo Sakakura who Perriand knew from their common time in Le Corbuisier's atelier, Charlotte Perriand was invited to Japan.

In 1933 the German architect Bruno Taut had spent five months advising the Japanese on consumer products, and as with Taut Charlotte Perriand considered Japan's strength, and the key to future success, to be its indigenous techniques and materials.

A concept that a decade earlier would have made a certain Charlotte Perriand crease with laughter.

Until the mid 1930s Perriand had been an ardent supporter of what she referred to as the revolutionary material steel. And an equally ardent opponent of wood, indeed in her 1929 text "Wood or Metal ?" she denounced it as a "... vegetable substance, bound in its very nature to decay,...." and expressed her belief that "The FUTURE will favour materials which best solve the problems propounded by the new man...." (original capitalisation)

However by the mid-1930s, and unquestionably influenced by both the new vernacular thinking sweeping the European Modernist movement and also the work of Scandinavian architects such as Alvar Aalto, work that largely answered many of her criticism of wood, Perriand was herself starting to create objects in the once derided "vegetable substance" and in her 1935 essay "Habitation familiale" she final gave up her unflinching devotion to steel for a position advocating a choice of materials based on the premise, "each in its useful place, technically and physiologically"

Sentiments that she was to apply to her contract in Japan.

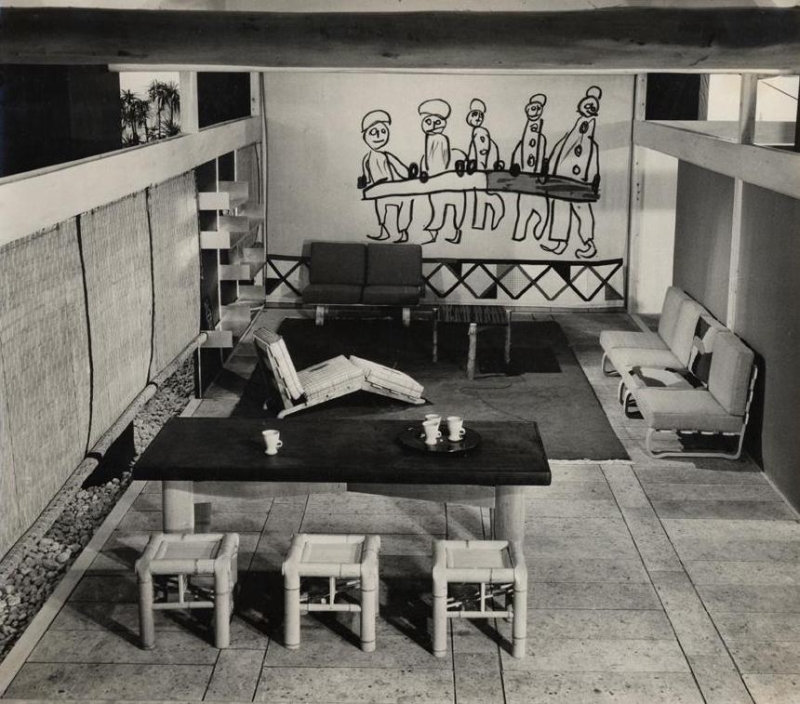

In the company of her guide and translator - a young student by the name of Sori Yanagi - Chalotte Perriand travelled extensively in Japan, observing and talking to local craftsmen and industry figures. Based on this research Perriand decided to focus on three areas: Local production that is suitable for export, local production that can adapted for export and new objects created using local materials and practices, including a number of her designs remade in the Japanese tradition. The most famous example of the final group probably being the bamboo LC4 chaise longue.

In 1941 Charlotte Perriand and Junzo Sakakura curated an exhibition of the results of the work under the title "Contact avec L'art japonais: tradition, selection, creation"

However in 1942 with Japan now at war with the West it had been looking to court just two years earlier, Charlotte Perriand was obliged to leave Japan as an "undesirable" alien.

The experience however remained with her and in 1955 Charlotte Perriand returned to Japan to organise the exhibition "Proposition d'une synthèse des arts" for which she created several objects specifically intended for production in Japan by Japanese craftsmen - most notably the chair "Ombre".

Charlotte Perriand et le Japon at the Musée d'Art Moderne de Saint Etienne Métropole promises to bring all these moments and experiences together in an exhibition which aims to present the most comprehensive exploration ever assembled of the role played by Japan in Charlotte Perriand's biography.

Featuring objects displayed at the 1941 "Contact avec L'art japonais: tradition, selection, creation" exhibition as well as works created for "Proposition d'une synthèse des arts" Charlotte Perriand et le Japon also presents photographs, archive documents and period art pieces, including a tapestry Perriand created in Japan and which has only recently been re-discovered. In addition objects by the likes of Fernand Léger or Le Corbusier will also be exhibited to help set Perriand's work in the context of the period.

Following on from the 2010 exhibitions "Charlotte Perriand und ihre Spuren in Brasilien" at the Gewerbemuseum Winterthur and "Charlotte Perriand: Designer, Photographer, Activist" at the Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich, we have the suspicion that an unseen hand is busy organising a sort of "Charlotte Perriand Retrospective Jigsaw", with the various pieces to be found strewn across the globe.

A concept we're quite happy with. Although it would obviously be good if someone could bring all the pieces together in one location.

Charlotte Perriand et le Japon can be viewed at the Musée d'Art Moderne de Saint Etienne Métropole until May 26th 2013.

Full details can be found at www.mam-st-etienne.fr