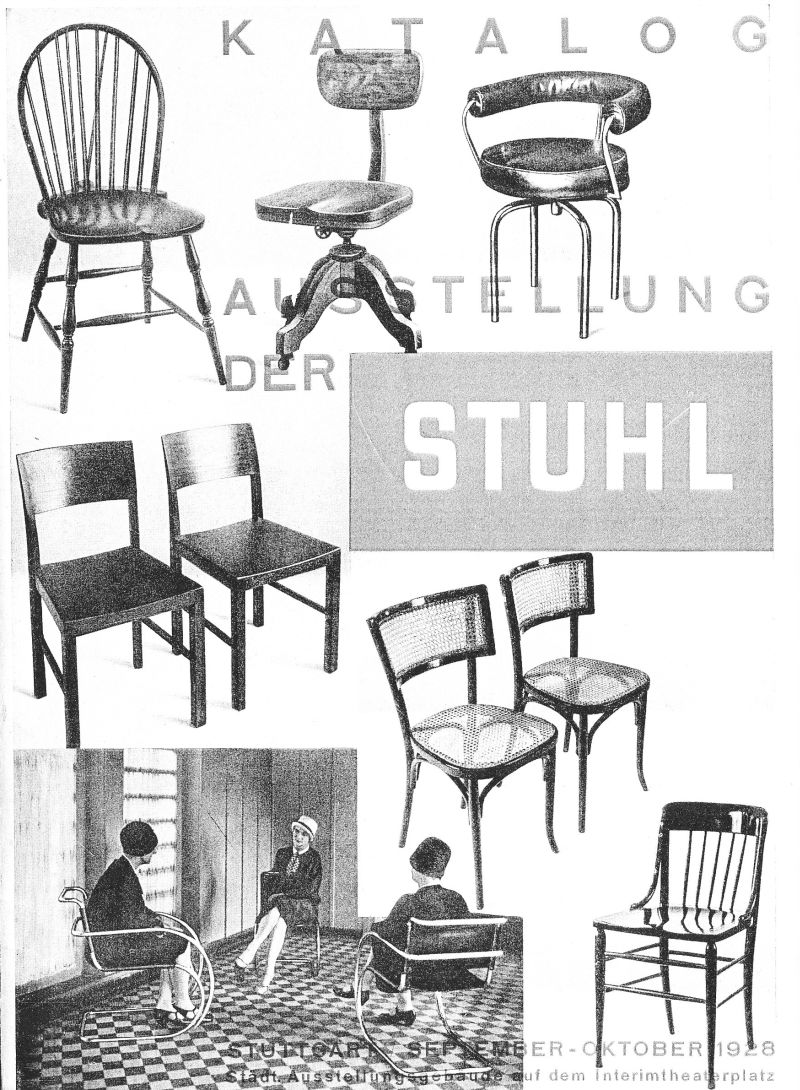

"The exhibition will principally present simple, functional and comfortable chairs for the home, office and garden"

With this clear note of intent opens the catalogue to the exhibition "Der Stuhl" that took place in Stuttgart from September 15th until October 15th 1928.

Organised by the Württembergische Gewerbeamt - the trade office responsible for the greater Stuttgart region at that time - "Der Stuhl" featured some 400 objects from over 50 international producers and was conceived with the aim of presenting an overview of those simple, comfortable chairs that were available at the end of the 1920s.

And the word "available" is important. All chairs exhibited had to be available for purchase over normal sales channels.

Museum pieces were strictly excluded from the exhibition; an ironic thought given the number of the exhibits that now form the core of any respectable design/applied art museum's permanent collection.

What "Der Stuhl" however also does is offer a unique snapshot of an important moment in the evolution of European architecture and design thinking.

Coming so quickly as it did after the exhibition "Die Wohnung" and the associated Weißenhofsiedlung Stuttgart and presenting works premiered there together with products either created before the First World War or products which although on the market were still going through the final development stages and weren't 100% ripe, "Der Stuhl" embodies the crossroads at which design and architecture found itself at that time.

For example, whereas wood formed the basis of most of the chairs displayed - including many demonstrating more than a knowing nod to Michael Thonet's wood-bending process - metal was starting to make clear inroads.

In addition the first evidence of large scale mechanical production is also visible. On the one hand an accompanying fringe exhibition presented, for the first time, "Special Machines for Chair Production", while on the other the form and construction of many of the pieces indicates that they had been created with the aim of being mass machine produced rather than via traditional, labour intensive, craft processes.

A fact that alludes to the title of this post. With the acceptance of a transition from craft to industry came the need to specifically design furniture that matched this new thinking. In that sense, and although the works on display were exclusively from architects and artists, "Der Stuhl" unquestionably marks the start of furniture design as a genre in its own right.

Yet despite these and other examples, our impression is that none of the visitors really understood the historical importance of the event.

Reading the catalogue, post-exhibition book and press-clippings of the day, one is aware of just how matter-of-fact and unspectacular the whole thing was. No-one seemed to be especially excited by what was on show. Just curious to see what the different producers had done.

In contrast any modern design collector with access to a time machine would probably have a heart attack if he unwittingly set the dials to Stuttgart 1928 and walked, unprepared, into the exhibition hall.

There were, for example, two chairs marked as being from "Architekt Rietveld, Utrecht" including an unpainted Red-Blue Chair. And that despite the fact the eponymous colours were added in 1923. We presume, but cannot confirm, that Gerrit Rietveld was looking to highlight the fact the chair could be mass produced, something that works better without the distraction of the colours.

Or the very first chair in the exhibition was listed simply as "Cantilever Chair, metal tubing and belting" from L&C Arnold GmbH Eisenmöbelfabrik Schorndorf. Only under the photo is the addendum "Design Mart Stam, Rotterdam" to be found.

The catalogue also features a very familiar looking swivel armchair by one "Charlotte Perriand, Paris".

The object is, presumably, the original B 302 Perriand created in 1927, and which later, after intervention from Pierre Jeanneret and Le Corbusier - and a little fine-tuning by all three - was re-released in 1929 as the object that would eventually become the modern Cassina LC7. A chair credited to all three, but marketed as being Le Corbusier.

A fact that transforms an innocuous catalogue entry into the most wonderful insight into the history of furniture design and for all into the history of a product we think we all know.

"Der Stuhl" exhibition literature is full of such moments. Moments which present furniture design as a passionate, personal topic rather than hard-nosed, calculating business.

But moments which also underscore just why "Der Stuhl" is so important as historical documentation.

It is almost certainly over-egging the pudding somewhat to call "Der Stuhl" the greatest furniture show of all time, and certainly amongst the highlights there is also a lot of mediocre "ballast" to be found. However, in terms of the range of products on show, the collection of "designers" presented and the central place many of those objects and their creators have gone on to take in the history of design, you'd have to go a long way to find a more significant, stimulating and downright charming exhibition than "Der Stuhl" in Stuttgart.