About a thousand years ago we asked our favourite Portuguese designer Rui Alves aka My Own Super Studio about the use of colour in his work and he answered "I try not be afraid of colour. Portuguese art and design has a tradition of using lots of colour and so for me it is natural to use colour."

Anyone wanting to get a feel for what Rui means need only spend a day travelling on the Lisbon underground.

While there are a lot of cities where using the underground system is more visually stimulating than visiting the local art galleries: the underground stations in Lisbon are particularly rewarding.

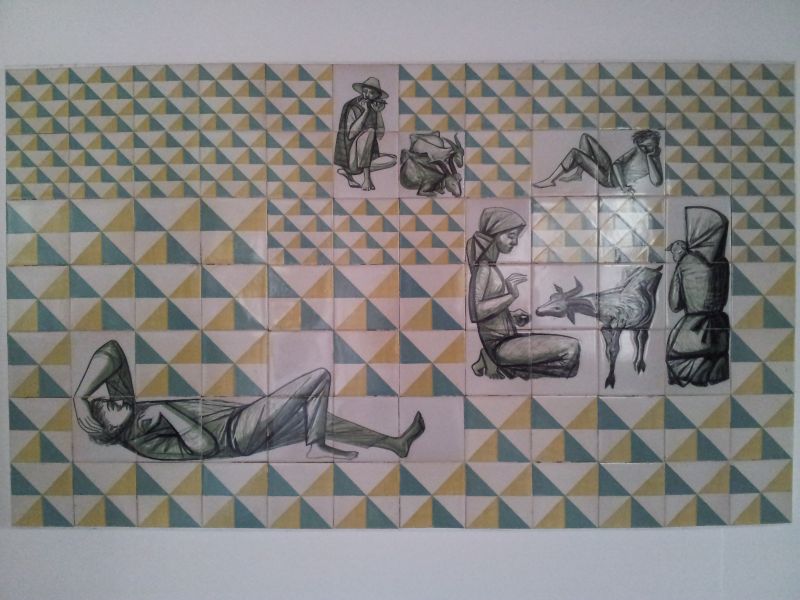

Not least because the chosen medium is decorative tiling, azulejo - an artistic form that is as Portuguese as sardines, discovering new continents or Fado.

The artist responsible for the majesty of the Lisbon Metropolitano azulejos was Maria Keil. A woman just as fascinating as her work. And an artist who sadly left us on June 10th 2012 aged just 97.

Born in Silves in 1914 Maria Keil studied painting at the Escola Superior de Belas Artes in Lisbon and over the course of her career worked as a painter, illustrator, engraver and textile designer. Had she been born fifty years later she probably would have been simply classed as a graphic designer.

In 1933 she married the architect Francisco Keil do Amaral and together they formed one of the most important Portuguese design teams of the Modernist period - Franscisco designing the buildings, Maria the interiors. Among their most important projects are the original Lisbon Portela Airport and the Gold Medal winning Portuguese Pavilion at the 1939 Paris Expo.

And so when in the late 1950s Francisco was commissioned to construct stations for the new Lisbon underground system it was not entirely surprising that he asked his wife to bring colour and life to them.

Nor was it entirely surprising that Maria Keil chose azulejo as her medium of choice.

First introduced to Portugal in the 15th century decorative wall tiles quickly established themselves throughout the country, not only for their colour and ornamentation but also on account of the fact that they both helped illuminate rooms through reflection of light and also helped cover the unsightly walls of the buildings. And while over the centuries their popularity naturally rose and fell depending on the mood of the nation or the political situation, azulejos never completely vanished and remain today an inescapable component of all urban environments: a stroll down any street in Lisbon, for example, being akin to a stroll through an open air art gallery. Its also of course one of the reasons Portugal always seems to shimmer brighter than anywhere else. It's the reflection from all the multi-coloured tiles.

In the first half of the 20th century azulejo was in one of its troughs and generally considered to be little more than a decorative historical artifact, and although their use by Art Deco and Art Nouveau artists meant that they remained contemporary, they played no real role in architecture.

The 1953 International Union of Architects (UIA) Congress "Architecture at the Crossroads" in Lisabon changed that.

Not only did it introduce Portuguese architects to current theories on using traditional, local products and processes in your building work, but also presented numerous examples of the use of azulejos in the brave, new, modernist rebuilding of Brazil being undertaken at that time.

And so in a textbook example of post-colonial theory, Portuguese modernist architects re-imported an updated interpretation of azulejo from the former colony.

Francisco Keil do Amaral participated at UIA 1953 and he and his wife readily embraced these new impulses. And so whereas pre-1953 Maria Keil's catalogue shows no examples of azulejo, post-1953 she created azulejo designs for many of her husband's projects including Luanda Airport, a housing estate on Av. Infante Santo in Lisbon and the refectory of the UEP holiday complex in Palmela.

And did so with such a confident naturalness one could almost believe that it was all she had ever done.

An important factor in all Maria Keil's azulejo work is the masterly use of colour. Sometimes lots, sometimes less but always used in such a way that it perfectly supports the composition or graphic. Good use of colour isn't about lots of colour or bright colour. It's about the correct amount of the correct colour in the correct place.

Despite the scope of Maria Keil's azulejo work, it is however for her designs in the Lisbon underground that she is best known; works that with her passing stand as a more than fitting memory to her artistic sensitivity and understanding of Portuguese history and tradition.

The designs for the first 11 stations were completed with the construction of the stations from 1957-1959. Over the coming decades a further 11 followed, the last being for the newly renovated Estação São Sebastião in 2009.

Reminiscent of street art Maria Keil's installations are predominantly based on randomly repeating geometric forms supported through a use of colour that ranges from the monotone, for example at Estação Restauradores or Estação Intendente over carefully considered gradients of hue and shade and onto full on in your face pieces as wonderfully exemplified by Estação Rossio.

As artistic works Maria Keil's Metropolitano azulejos are not just wonderful examples of mid-20th century visual composition, and works which are on a par with anything the likes of Ray Eames or Alexander Girard were creating at the time, but much more, through their use of shapes and forms drawn from five centuries of Iberian decorative tile design are also fitting and respectful modern interpretations of an artistic form that lies at the very heart of Portuguese craft tradition.

And make a day ticket for the Lisbon underground one of the best cultural investments you can ever make.

Thank you Maria Keil!