Last August we made an ill-fated trip to Copenhagen and CODE 10.

A trip that caused us to ponder the question if Danish furniture design is still relevant.

To help us explore this point a little further we decided to speak to two young Danish designers and ask them for their views and opinions on the current state of furniture design in Denmark.

Monique Engelund and Jonas Pedersen both studied architecture in Aarhus, graduating with a degree in furniture design. And no they didn't change course half-way through. The course in Aarhus is structured such that one studies "traditional" architecture for the first two years. And then specialises in either architecture or furniture design.

The term for people such as Monique and Jonas we learned is "furniture architect"

Not only a delightful term in its own right; but a phrase that for us wonderfully encapsulates a central reason why mid-20th century furniture design produced so many design classics.

It's practitioners were architects. Who trained like architects. Who thought like architects. Who designed like architects.

For Jonas Pedersen the reason why specifically Denmark profited so much from this global phenomenon was a question of material choice. "In the 50s and 60s when Danish furniture design got really big there was a large number of really skilled architects in Denmark, and they principally worked in wood and created a very unique style"

A style that went on to establish itself as a by-word for quality and innovation, and which established household names such as Wagner, Jacobsen or Juhl.

But in how far are these "old masters" a burden for the current generation of Danish designers; a generation who weren't born as the tradition of Danish furniture design was being written.

A big problem says Jonas. "Many people still think that Danish design is defined by the past. Which can be really annoying because many people think the good stuff is only the stuff from back then. And so we have to fight against that."

Monique Engelund has already made her own experience with such attitudes. Responding to an advert from a company in China looking for a "new", "young" "wild" "fresh" Scandinavian designer she submitted some examples of her work. "But all they wanted was wood furniture because they thought that's what we do!"

Que a communal shrugging of shoulders in the room.

But what of the new generation. What do they do? What motivates them?

Faced with the challenge of designing in the 21st century Monique highlights the problem of perspective as a designer. In the 50s and 60s many young designers were concerned with rebelling against conformity and fighting for their creative freedom. A freedom today's young designers have, but must first learn how to use.

"At Uni" says Monique, "we are actually often advised to be rebellious, which of course makes being so, quite a paradox."

For as we all know, what's the point in rebelling in an open space. One needs borders to push against.

Such problems are of course not limited to Denmark. We're a global society.

The new generation of designers need to learn to formulate the question they want to ask society, to define the borders of what society will accept, before they can start presenting answers.

And maybe that's part of what we missed at CODE 10.

Innovation. Risk. Youthful rebellion. And if you want to get all old skool punk about it - a manifesto.

All of which made our hearts beat a little faster as we slapped a miniature Panton Chair on the table and asked: "International design or Danish design?"

Jonas: "That's from Mars..."

Monique: ".... that's certainly not typical Danish. I think the development of that chair is European, I mean we can't take any credit for it!"

For many non-Danes, however, the Panton Chair is the very epitome of contemporary Danish design. The work however was not only criticised and mocked by Panton's Danish contemporaries at the time, but Panton would never have been able to find a producer in 1960s Denmark.

Or indeed, based on Monique's experience, in 21st century China.

Ironically. Given the volume of illegal copies originating there.

Whereas the generation before Verner Panton found their success in the creation of a unified, definable conservative form language based around the same one material; Verner Panton found his success, and ultimately revitalised Danish furniture design, because he used new developments in production and material technology to rebel against these established perceptions.

Which could lead one to the conclusion that if Danish design is to remain relevant in the future they need designers who, in effect, rebel against Panton.

And are they? In which direction is Danish furniture design going at the moment?

Listening to Jonas, Monique and their contemporaries one gets a good impression of young designers who no longer see a contract with a big name international producer as their ultimate goal and who understand their work as solutions to problems rather than "just" products. Or as Monique so eloquently puts it, " I think there is a tendency of combining design with other disciplines be it sociology or ecology, and so looking for the deeper meaning to your products"

If that isn't a rebellion against pop art revivalism!

But perhaps more importantly one gets an impression of young designers for whom "Danish design" is no longer a design style. But a simple geographical indicator.

Similarly there are also new, young Danish producers such as Hay or Normann Copenhagen who have also grasped this and who tend to have much more international rosters than was the case in the golden age of Danish design; who however remain open to young Danish designers.

And such producers coupled to a continuing stream of talented and intelligent furniture architects such as Jonas Pedersen and Monique Engelund certainly gives us hope for the future of furniture design in Denmark.

Maybe CODE 10 just came to soon!

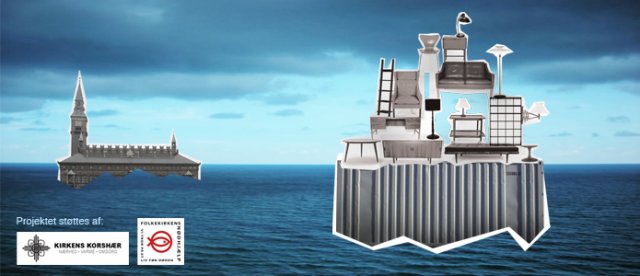

During Copenhagen Design Week Monique Engelund is presenting Noah's Ark, a joint installation with Sophie Alexandrine which explores the ecological burden of over consumption in the context of furniture design.